What about our identity as the crown of creation, as gardeners of logoi, as priests? How do we recover it? How can we see again?

Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin.

Psalm 51:1

Our Identity

We are created this way, it is who we are—these gardeners and priests and artists … But we have been born into a fallen world and tainted by its sickness, its diseases. We call these the passions. How we have mechanized to deal with the illness of the world has enslaved us to our passions, to our self-love; for in a world without love, we have learned that the first point of survival to is to love yourself before you can love anyone else. The problem is you can’t apprehend the world through self-love and the passions that go along with it: lust, greed, gluttony, pride, anger, and envy. These passions blind us to the world around us, to the inner logoi of things because we can only see ourselves.

If the contemplation and Eucharist is likened as a circle with us in the middle, and we are an integral part of that cosmic cycle of apprehending God in creation and offering creation back to God, then sin, illness, death is the way of stepping out of that circle and objectifying creation through the lens of our desires, through the orientation of our self-love. Larchet explains,

The passions lead man to turn in on himself and see in things nothing beyond their appearances. They prevent the indirect vision of God through His creatures, and, far more so, they block that direct spiritual vision imparted by the Spirit which the Fathers call theologia. The passions are founded on the egotistical love of oneself which the Greek Fathers call philoutia. They are the obstacle to love: the love of God, the love of neighbour and the love of creatures in God, whereas contemplation and the Eucharist bear witness to love, and presuppose its presence (32-33).

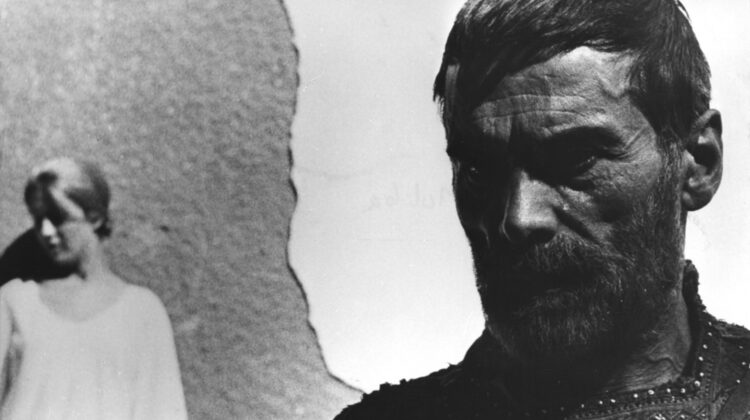

It is thus through our passions that we have abused the world and our fellow humans by treating them as objects of our own passions, and by not seeing the image of God in them. You can see it all around you, especially in what is misconstrued as art, whether music or movies or fashion … There is a great deal of decay and degradation coming through the arts in our times. There is a profound deformation of the image of God portrayed through the arts. Just look at pop music album covers to see it, or in music videos, or in the movies considered ‘works of art’ … What’s going on there? Where is the sacred in popular art? Where is the holy? The image of God spread out on a flat one-dimensional screen and degraded, and stripped of dignity, of the very thing that makes him or her human. Like a plague that runs amok leaving dead bodies everywhere gazing through you with their bloated bulging eyeballs.

The Short Circuit

And the problem is the toxic world is held out to us as something desirable, as something somehow fatalistic, something we just have to consume, have to see. Literally defecate in a hole and call it art. Defame and degrade another human being and call it art—record it on your iPhone and send it viral and have your time in the limelight while the person objectified enters rehab or kills himself. And then there’s the saddest of all: suicide as art …

What are we doing? … And why are we consuming it to the extent we are? Is that really us? Is that really how we’ve been created to be? Is that the vision of man held up to us as real and true? This fake vapid world of smoke and mirrors called ‘reality’?

And look at the suffering of living this way; look at what we’ve done to the world simply from an ecological perspective. When the value of something is determined by my own obsessions and desires, then its only worth is how it fulfills a given urge—it’s how we treat nature and it’s how we treat each other.

But what about our identity as the crown of creation, as gardeners and priests, as artists? … How do we recover that identity? How can we begin to see again?

The Movement of Repentance

Larchet comments:

The salvation of nature can only be accomplished through men whose mentality has been purified. To play their part in this task, as far as is possible, they must change their mentality and way of life and behaviour. Repentance (in Greek, ‘metanoia’, which means change—‘meta’— of the state of mind—nous—is of prime importance. Every spiritual undertaking should start with repentance (83).

Repentance is different from being gaslit by global think tanks into shame and guilt. The popular world as it were is full of propaganda that seeks to foist guilt on people for damaging the earth, all as a ploy to show that humans are a burden on the earth and must be eliminated. We are told to consume less so that those in power can consume more. The climate change narrative is antithetical to the vision of God for man, and His intentions for humans to live in and through His created world. So part of the repentance is reframing how we see the planet and how we live in and through it. It is seeing how we have not lived as stewards of the earth, and finding ways to bring our lives back into balance with it.

For a Christian, the world is not some ill-defined and general entity, but is made up of the concrete beings of creation. … [Christians] should first and foremost repent for all their failings towards the creatures which make up the environment. First and foremost they themselves should repent for all their own failings towards nature: the damage they have caused, their lack of proper care for it, and their failure to behave towards it virtuously and so to set a good example (83).

The true root of the ecological crisis is in the heart. It’s in the way we use the world for our own desires, and not as stewards. Instead of gardeners of the logoi, we participate largely uncritically in a system of exploitation of people and natural resources. But we can’t simply engage in repentance in theory or as an ethical orientation. We must engage in this activity as an ethos—as action that comes from our hearts in relationship with the Logos Himself:

It must be based on the faith that it is God Who gives worth to nature since He is its Creator. He protects it with His Providence insofar as man’s liberty, which God respects and allows. He is also its end through the logoi which it bears within. Nature can only be respected when the sacred and transcendent dimension of its relation to God is recognized (91).

Becoming More Human

To become artists we need to become more human. To become more human means we are ever moving towards understanding and living out our vocation in the world: To be contemplatives of God in all creation, and to be priests by offering it all back up to Him in thanksgiving. In this cycle of contemplative and priest, this Eucharistic orientation to the natural world, we will find our healing from the passions that jaundice our vision of God, ourselves, and creation. To begin this we must learn to live a simple life, like that vision laid out by the Fathers of the Church and, quite simply, monastic life. Or in Larchet’s words, “everyone should become an ascetic in the strictest meaning of the term, which implies effort, renunciation, and privation based on temperance and sacrifice”(85). This kind of ascetic life leads one into a movement of cleansing the passions and growing in virtue. To begin repenting and changing our course of life, we don’t need to do anything complex. We can learn to live a simple life again. We can pursue moderation and self-control in what we do and what we consume.

The Fathers see temperance … as a cardinal virtue. It implies self-control and especially moderation in food and in the use of all things which procure bodily comfort and pleasure. Sacrifice means giving up some of our goods, some of our wealth, and some of the things which give us a life of ease. It also implies a change in who we are insofar as this depends on what we have (85).

Such a life of contemplation and thanksgiving, of living simply, of divestiture and sacrifice will foster a growth in love. And when we grow in love, we are able to see the world more clearly. And when we see the world more clearly, we can artistically represent it.

The Fathers saw that the cleansing of the passions led to the growth of love, which would enable man to contemplate nature truly. He would be able to see the presence of God there through His energies, and the logoi of His creatures, and to see the relationship of each creature to God. Love and contemplation reinforce each other. By loving creation, man perceives God, and seeing His presence in creatures he loves them even more. Dostoevsky writes of this: “Love all creation, as a whole and in its elements: each leaf, each ray of light, the animals and the plants. By loving all things you will understand the divine mystery within them. Once you have understood, you will grow in knowledge each day, and will finally love the whole world with a universal love”(90).

Conclusion

The Christian faith, in all its fullness, offers us the potential to grow in loving union with God, the cosmos, and each other. We are beings created to become gods, to become divine beings, heavenly hosts. We are created with the capacity to see the fullness of creation, to understand the essence of things, and to represent it in all sorts of creative ways. We are created with freedom to apply ourselves to cultivating God’s creation, and cultivating love for it and for every created being. Our Christian faith, again in its fullness, offers us the opportunity, the occasion, to become fully alive and fully ourselves by becoming more human. And we become more human the more we become like Christ, like God. It is a true holistic way of being that is the a priori point of departure for creating art in the first place because it is the only way that we can have the vision, the ability to see, reality as it is.

Through the sacraments of the Church, we are united to God by Whose Spirit we are filled and in Whose Spirit we are sent forth to be light to the world. Through a Eucharistic way of being, we become mediators between God and creation, thus fulfilling our true vocation on this earth. Again, art becomes tertiary. As Arvo Part says, we must purify the heart so the soul can sing in harmony and beauty. When our hearts become pure, we grow in love and harmony with all of creation. We seek to love it, nurture it, and, through our art, represent it. We seek wholeness and completeness and harmony in our lives, in how we orientate ourselves to the world, which also seeps into how we create and make things. And the more we seek harmony, wholeness, the more we are healed; and the more we are healed, the more our vision is purified and the more we can see the essence of what surrounds us, and the more our living and creating and being become united through a “cosmic liturgy” into our true vocation—to become saints by becoming ourselves. And thus art becomes one way we take the matter of God’s creation, see its internal logoi, and offer it up to God through our (re-)making, our refashioning; and through our art, we create occasions for others to encounter God.

Art, then, is created out of an authenticity of being and becoming, and thus we become the true works of art, which is God’s intent for us in the first place and what Christ gave His life, His death and resurrection, to unite us with. Through our Christian faith, in all its fullness, we are brought back into the circle of Love, into the circle as mediators between God and His creation, and thus enter into the fullness of life, of God, and being ourselves.