Flannery O’Connor shows us not only how to pray, but also how to find Beauty in our writing by getting ourselves out of the way.

What Fake Writing Looks Like

It’s crazy what ‘writing’ has become in the madness of AI–when people are churning out documents and texts and books and scripts at the speed of light with nothing really actually hand-written but a bunch of ‘prompts’, or sets of criteria for the machine to search and connect with into fairly basic statements that sound all too fake and cold. And people call this writing.

Probably no different from the emergence of Ikea when furniture was a craft and people worked hard to create beautiful and functional pieces because they were artists and craftsmen. Now, furniture is largely mass produced and sold on the cheap. It is the same with words: they are rapidly and mass produced and largely cheap.

Seeking the Beauty in Real Writers, Like Flannery O’Connor

It is in this context that I love to read real writers; people, human beings, for whom writing is not cheap but something one labours over, something one does for the love of it, something one is compelled to do because one’s soul is prompted by God. There is so much for us to learn from these writers of the recent and distant past; for those of us who see our writing more as an act of recovery or re-discovery, of discovering, reclaiming, recovering what has been lost.

There are writers we return to again and again for different times and different reasons. In thinking a lot about this AI world and the cheap rapid generation of words, I find myself returning to Flannery O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal. O’Connor was a true writer and true artist who lived poetically–a life of poiesis, more in the understanding of St Porphyrios, which is living a poetic life of beauty, of seeing the beautiful, as well as a place of repentance and seeking purity before God.

Back to Flannery O’Connor’s Prayer Journals

A couple of O’Connor’s prayers really struck me–so much so that I was compelled to write about them.

The Prayer Journal, as I’ve written before (link), is O’Connor’s intimate prayers to God. The prayers are mostly about O’Connor’s existential tension between her desire to be a writer, an artist, and the awareness of her ego, her self, that is trapped in sins and distorted thoughts that darken or distort the beauty, the truth, and the goodness of what she sought wholeheartedly to communicate.

Her writing is prayer and her prayer writing. Take a look at this passage …

Dear God, I cannot love Thee the way I want to. You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see and my self is the earth’s shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon. The crescent is very beautiful and perhaps that is all one like I am should or could see; but what I am afraid of, dear God, is that my self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the whole moon, and that I will judge myself by the shadow that is nothing (A Prayer Journal, 3).

The Beauty of God is likened to a crescent moon, not a full moon but merely a crescent–the rest remains largely hidden because her ego, her self, her desires, ambitions, desires overshadows the rest of what God wants to reveal to her in His Beauty; and her ego threatens to inflate so much that it blocks out even the little glimpses of Beauty that she sees.

And worse yet, worse than the darkness that her ego has created, is that she will then judge herself by that shadow, that inflated image of herself–a shadow that is really nothing but a kind of chimera, a fantasy, something of the imagination–rather than what is real. This is the realm of complete self-delusion which is the death of authentic art.

And then this stunning line of her prayer that you can feel within your own soul and cry out and pray in more desperation than hope, that is more of a confession than a true act of repentance–but we must start somewhere …

I do not know you God because I am in the way. Please help me push myself aside.

Please help me push myself aside. … How many of us pray like this before or while we are writing? How many of us instead yearn, like O’Connor admits here, to make a name for ourselves, to be the one to receive credit for that one good line or that story idea or that book that in our minds is better than the one that received the Booker Prize … How many of us want to inflate more of ourselves because we feel too small and our voices and our words are too small for the big fish in the seemingly large pool we’re floundering in?

Repentance, Compunction Becomes Creative Act

But this act of contrition, of repentance, of compunction shot through the creative act is art, it is what writing is. You can’t prompt your way in and out of that existential place before yourself and God–you just can’t. It’s the hunger and the thirst and the desire for purity, and out of that purity a taste, a glimpse, an encounter with Beauty that is the work of art, that is poiesis, that is creativity.

Here’s another by O’Connor that shows the creative act as spiritual encounter …

Dear God, I am so discouraged about my work. I have the feeling of discouragement that is. I realize I don’t know what I realize. Please help me dear God to be a good writer and get something else accepted. … Contrition in me is largely imperfect. I don’t know if I’ve ever been sorry for a sin because it hurt You. That kind of contrition is better than none but it is selfish. … All boils down to grace, I suppose. Again asking God to help us be sort for having hurt Him.

And in words of her prayer that prefigure the insurmountable pain and disintegration of her body over the years that will follow, Flannery confesses …

I am afraid of pain and I suppose that is what we have to have to get grace. Give me the courage to stand the pain to get the grace, Oh Lord. Help me with this life that seems so treacherous, so disappointing (10).

Grace That Comes Through Pain

It is no wonder that grace is arguably the leitmotif of O’Connor’s stories–but not a lovey-dovey grace that is all lollipops and rainbows.

No. It is a grace that comes through pain, whether inflicted upon one by life, or at the hands of someone else.

Grace comes hard and shakes us up, bursts the bubble that has inflated over God’s crescent moon, whacks us over the head, throws a hard text book at our foreheads then leaps upon us striking us repeatedly while we’re kicking and screaming from our backs. This is the process, for O’Connor, of salvation; this is the process of receiving grace; and this is the process of creating good writing–body and soul united in an act of creating before God.

And what happens when we live this way, when we struggle to cast our egos out of the way, when we wrestle to see God and to encounter Beauty, God gives us things to do, which may include writing …

Dear God, tonight it is not disappointing because You have given me a story. …

We wait. We go deep into ourselves, into our illusions, into our sins, into repentance and contrition … and God gives us our heart’s desires, but in the right way. But we then have to understand where that gift comes from and who has given it to us.

Writing as Prayer, as Beauty, as Sub-Creation

O’Connor continues in this prayer and illumines us to how we ought to approach our own writing …

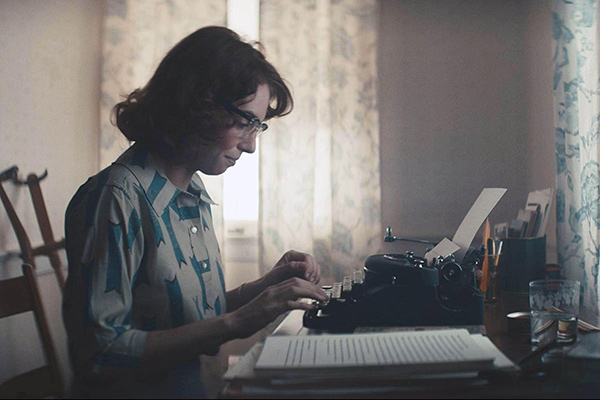

Don’t let me ever think, dear God, that I was anything but the instrument for Your story–just like the typewriter was mine. Pleas let the story, dear God, in its revisions, be made too clear for any false and low interpretation. … Please don’t let me haver to scrap the story because it turns out to mean more wrong than right–or any wrong. … Perhaps the idea would be that good can show through even something that is cheap. I don’t know, but dear God, I wish you would take care of making it a sound story because I don’t know how, just like I didn’t know how to write it but it came.

A big part of moving out of the way is knowing the One Who inspires her and writes through her, just as she writes down the words through the instrument of the typewriter. And you can see here the clarity, the goodness she desires in her prose is a reflection of the clarity and goodness she wants to become herself. Back to all writing being re-writing, iteration, and the spiritual life, the work of getting ourselves out of the way, being a process of iteration too. A large part of that way of living, as O’Connor includes in her prayer, is thanksgiving …

Writing as Prayer, as Thanksgiving

Anyway, it all brings me to thanksgiving, the third thing to include in prayer. When I think of all I have to be thankful for I wonder that You don’t just kill me now because You’ve done so much for me already and I haven’t been particularly grateful. My thanksgiving is never in the form of self sacrifice–a few memorized prayers babbled once over lightly. All this disgusts me in myself but does not fill me with the poignant feeling I should have to adore You with, to be sorry with, or to thank You with (11-12).

Even in thanksgiving she’s repenting for her lack of fervency, her lack of real love, and her “memorized prayers babbled over lightly,” she’s peeling back the layers of darkness, of shadow, to yearn to see the crescent moon grow and grow.

My mind is the most insecure thing to depend on. It gives me scruples at one minute and leaves me lax the next. If I must know all these things thru the mind, dear Lord, please strengthen mine.

Here O’Connor asks for strength of mind, not to gain more ambition, but to be able to understand more of what God wants to show her, more of the grace He wants to extend to her, more of his Beauty he wants to reveal to her. After repenting of her lack of thanksgiving and her lack of real love, she gives thanks to God and to St Mary …

Thank you, dear God, I believe I do feel thankful for all You’ve done for me. I want to. And thank you dear Mother whom I do love, Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

Here the young O’Connor teaches us not only what real writing is, but what real prayer is.

May the Lord guide us to become people who sincerely pray first, and people who write, who create, out of the longing, the repentance, and the thanksgiving that extend out of what is revealed to us by the One Who loves us and pays attention to us more than we can imagine.

I think that is in keeping with O’Connor’s prayers–that she prays to the God who looks down at her through the eyes of Love and Beauty, Goodness and Truth.

May we see God, our prayers, our writing all as that very same thing, and in that same way too.