Dostoevsky shows us what it means to write with prophetic passion. This post is a glimpse into how “the last word” became The Brothers Karamazov.

Lord who may abide in Your tabernacle? Who may dwell in Your holy hill? He who walks uprightly, and works righteousness, and speaks the truth in his heart …

Psalm 15:1-2

What One Might Find In the Meagre Introductions of Books

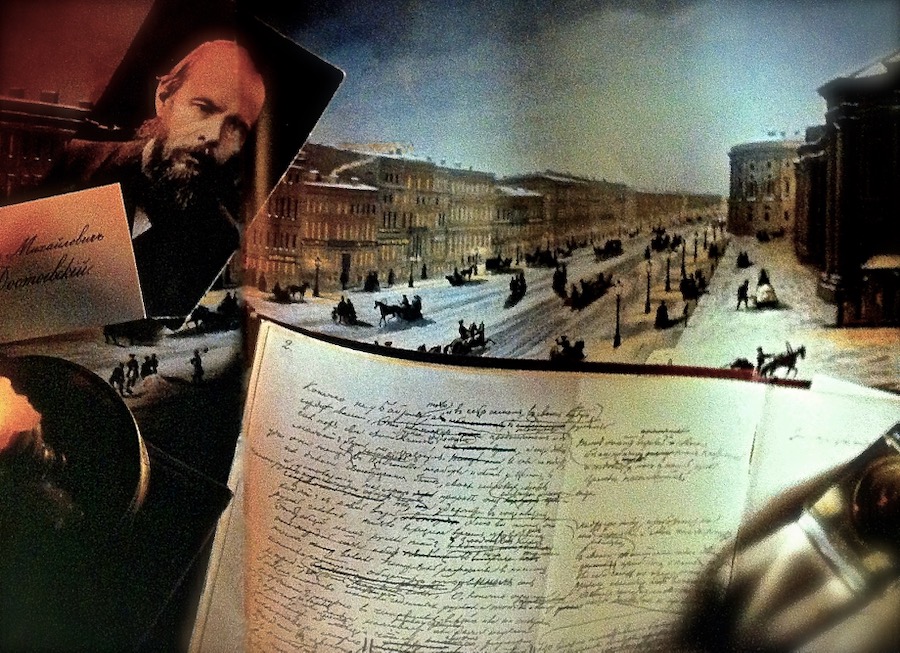

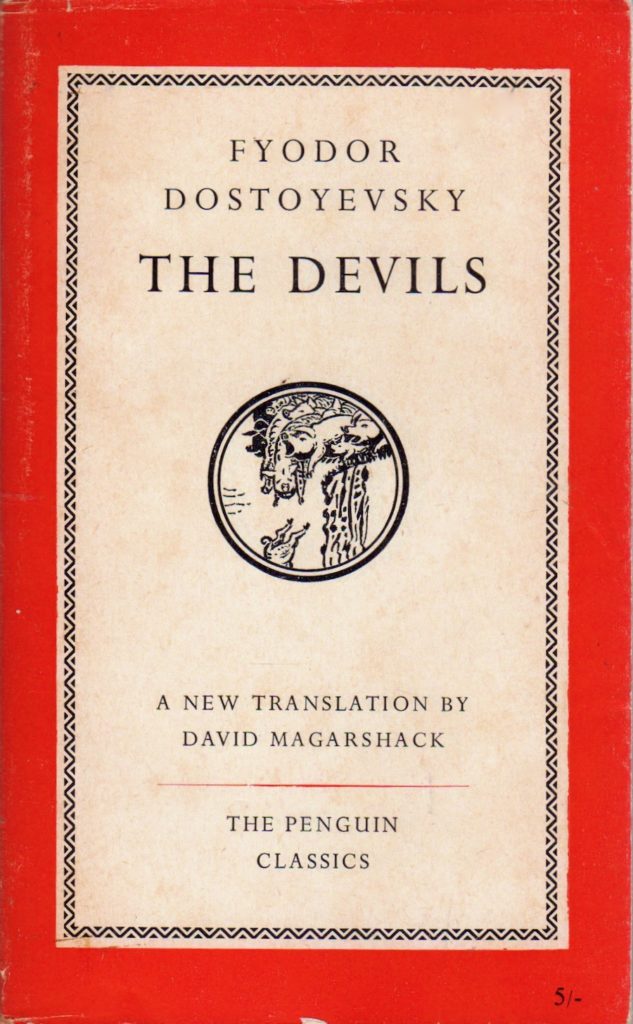

I was sitting on an airplane with a worn out copy of Dostoevsky’s The Devils in my hand. The plane was still on the tarmac, which is a perfect time to read. Perhaps you’re the kind of reader that goes right for the opening of chapter one, skipping over any prefaces or epilogues, etc. I tend to read the first sentence of the preface and head straight to chapter one, only to return to the front matter of the book half-way through said chapter–and that’s exactly what I did on this occasion of reading Dostoevsky’s The Devils.

Sometimes front matter can be lacklustre: a simple introduction to the book by the editor or translator, or one that discouragingly sketches out the yawning abyss between the Russian and English languages that renders the English translation nothing shy of a brutal murder of the original and a dog’s breakfast of a stitch job. But once in a while you read front matter that is actually inspiring, that contains something that you just need to write down somewhere. A nugget that grooves itself into your mind and keeps turning over in it again and again. This nugget offers a glimpse into the creative passion of Dostoevsky shot through with a deep drive for the prophetic.

I am thinking of writing a huge novel, to recalled ‘The Atheist’,” he wrote from Florence to his friend Mykov on 23 December 1867, “but before I sit down to write it I shall have to read almost a whole library of atheists, Catholics, and Greek Orthodox theologians.

Dostoevsky had the protagonist worked out albeit schematically, the providence of which he explains in the following:

I have the chief character. A Russian of our set, and middle aged, not very educated but not uneducated either, a man of quite good social position who suddenly at his age loses faith in God. … His loss of faith in God makes a tremendous impression on him. … He pokes his nose among the younger generation, the atheists, the panslavs, the Russian fanatical sects, hermits and priests; falls incidentally under the influence of a Jesuit propagandist, a Pole, and descends to the very depths by joining the sect of the flagellants. At last, he comes to Christ and the Russian soil–the Russian Christ and the Russian God.

Then while these images and scenes are swirling around Dostoevsky’s mind putting him in a hyper-aroused state, he makes sure to include this parenthetical injunction:

(For goodness sake, don’t breathe a word of it to anyone: I shall write this novel of mine and I shall say everything to the last word, even if it is the last thing I do!)

To Write to the Last Word

This “to the last word!” really struck me–the passion, the vision of Dostoevsky, yes indeed; but there is certainly something else bubbling up in him that was taking over him at that time of his literary life, namely the prophetic.

There was a message he had to write, that he had to get out of his heart to the Russian people. It is clear in the book that he was to write from this “and to the last word!”, namely The Devils, that he foresaw the rise of atheism and nihilism in Russia, and how those philosophies from the west–Germany and France in particular–were infiltrating the Russia of Christian Orthodoxy and the Tsars.

Dostoevsky continues his rant …

What I am writing now is a tendentious thing. I feel like saying everything as passionately as possible (Let the nihilists and the westerners scream that I am a reactionary!). To hell with them. I shall say everything to the last word!

One day earlier, Dostoevsky wrote to his friend Strakhov …

I am relying a great deal on what I am writing for the Russian Messenger now, but from the tendentious rather than the artistic point of view. I am anxious to express certain ideas, even if it ruins my novel … for I am entirely carried away by the things that have accumulated in my heart and mind. Let it turn out to be only pamphlet, but I shall say everything to the last word!

Dostoevsky Sometimes Yells Like Nietzsche

I don’t know about you, but I love when Dostoevsky goes on his rants, whether in his letters or in his actual novels. That part of his artistic voice is so powerful and dramatic. The only other writer I can think of who has as powerful a voice is Nietzsche.

Whenever I read Nietzsche, I feel like putting on ear muffs to try to drown out the yelling. It’s what I love about reading Nietzsche and Dostoevsky–they have a pulse, and draw you into their world. They are responding to their world prophetically. I recall a course from a Kant scholar at Stanford named Allan Wood on Nietzsche and Dostoevsky: you’d read the Brothers Karamazov along side of Thus Spake Zarathustra–or was it Genealogy of Morals? And while there isn’t much written about whether Dostoevsky had read Nietzsche, Nietzsche claims to have learned his psychology from reading Dostoevsky.

From Darkness to Light

Here’s more from the Introduction of my copy of the Devils on this book in which Dostoevsky was to say everything to the last word:

Dostoevsky had jotted down notes in 1870, the ideas of which would fuse the Atheist with the Devils, whose chief character, however, was not to be an ordinary civil servant, but a wealthy prince:

“A most dissipated man and supercilious aristocrat,” whose life was “storm and disorder” but who “in the end comes to Christ.” He was to be a man with an idea which absorbs him completely though not so much intellectually as by becoming embodies in him and merging with his own nature always accompanied by suffering and unrest, and having fused with his nature, it demands to be instantly put into action. The prince is greatly influenced by a well-known religious writer who greatly influenced Dostoevsky himself and who was to have figured in the novel. This writer’s main idea Dostoevsky defined as “humility and self-possession, and that God and the Kingdom of Heaven are in us, and freedom too.”

I love this idea for a novel, particularly coming from an artist such as Dostoevsky. It seems he wanted to impact his readers; he wanted to show the reader, indeed the world, the Way of Christ. Nihilism was eroding the spiritual identity of Russia. Rather than dancing around the subject, Dostoevsky was attacking it; but not only that–merely replacing one form of nihilism with another–but providing the way of union with God, His Church, and ones’ fellow man. One of the things I love about Dostoevsky is his novels are typically quite dark, but they are always moving the reader to light. This I believe is a model that fuses the artistic with the salvific.

From Devils to Brothers K

The theme of his great novel in which he would say everything to the last word was shelved for a more “tendentious” one. Indeed, Dostoevsky who was no stranger to money problems–one of the lingering themes in his writing–needed to make some money by writing something less serious and quicker than what his great novel would demand. Dostoevsky told his friend Makov,

What I am writing for the Russian Messenger now I shall finish in about three months, and then after a month’s holiday, I shall sit down to my other novel. It is the same idea I wrote to you before. It will be my last novel.

Dostoevsky went on to construct the novel that eight years later would become The Brothers Karamazov. At one point it was called The Great Sinner. It was indeed Dostoevsky’s final novel before his death, and arguably his very best.

Prophetic Writing

As Christians we are called to be kings, priests, and prophets. I’ve written a little on what it might look like to be a priest within the context of writing. What Dostoevsky shows us is what it means to be a prophet. Dostoevsky was writing in response to the storm he saw brewing in his time that would radically destroy Russia as he knew it. I believe he saw the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 quite clearly–he was indeed no stranger to revolutionary groups, having been in one for which he was sent to Siberia–and needed to draw public attention to it. Did he foresee the gulags and Stalin and 60 million killed? It wouldn’t surprise me.

What’s important is Dostoevsky had the vision, the guts, the passion to say everything he could “to the last word.”

If you’re reading this and you’re a writer, do you have this sense of purpose and vision and passion?

Are you currently working on a book in which you will say everything to the last word?

Are you seeing things in society, are there storms brewing on the horizon, that you see and that you feel you need to write it? That if you were to die unexpectedly and you hadn’t written that book that it would be most devastating?

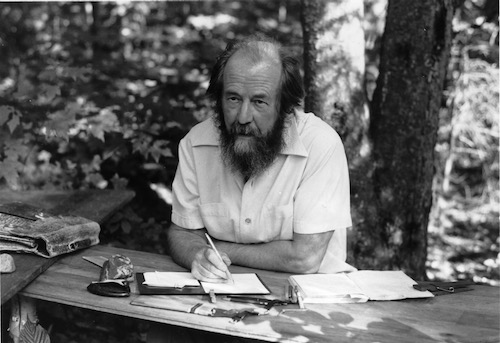

Solzhenitsyn and Truth

This reminds me of another favourite Russian writer of mine, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He too wrote everything to the last word. He writes in his Gulag Archipelago that men in the gulags would carry thousand page novels that they were writing in their memories until they were free to actually write it all down. The Gulag Archipelago was probably carried in this way by Solzhenitsyn.

One of my favourite quotes is this:

The simple step of a courageous individual is not to take part in the lie. One word of truth outweighs the world.

Another favourite one is this:

You can resolve to live your life with integrity. Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, let it even triumph. But not through me.

Let us all who write carry with us this burning passion of Dostoevsky’s “to the last word!”

And may the Lord strengthen us and bless the works of our hands.

One Response