What is the role of the artist in relation to Art itself? Pavel Florensky inspires us through his account of iconographers and their spiritual life.

Bless the LORD, all His works, in all places of His dominion. Bless the LORD O my soul!

Psalm 103:22

Pavel Florensky’s book Iconostasis is a dense work about iconography and the icon painter–so dense that it’s almost laughable that I would attempt to write about it in a single blog post. Nevertheless, there’s something important here that can be drawn from Florensky’s treatment about iconographers for all types of art–and for those who don’t practice art at all.

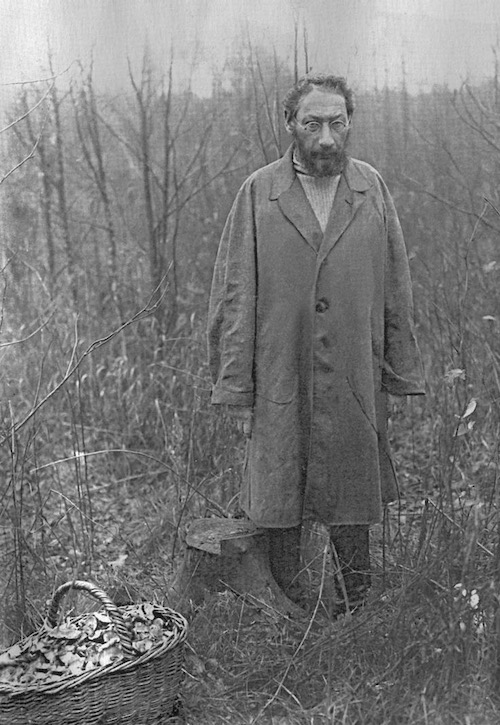

The Polymathic Priest

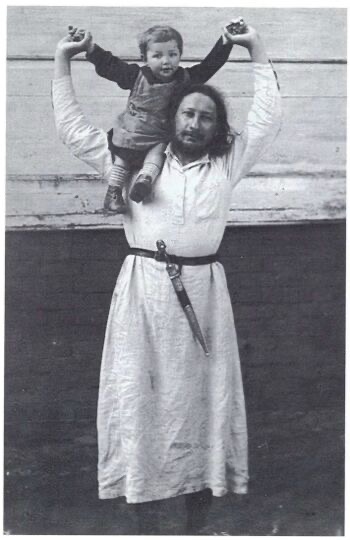

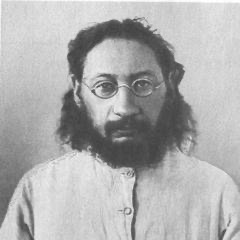

Father Pavel Florensky was a, philosopher, theologian, scientist, and art historian who became a priest in Russian in 1911.

Though never a parish priest, Father Pavel found true joy and healing in serving the Eucharist. For Father Pavel, to carry out the definitive Christian Mystery of simple bread and wine consecrated into Christ’s holy body and blood was “the only true way of union and love.”

His friend Sergius Bulgakov, one of the great Orthodox theologians of the twentieth century, said of Father Pavel that,

“The spiritual centre of his personality, that sun by which all his gifts were illumined, was his priesthood.”

Father Pavel wrote …

“Without love, the personality is broken up into a multiplicity of fragmentary psychological moments and elements … The love of God is that which holds the personality together”(Iconostasis, 13).

On August 17, 1910 Father Pavel was married. Between 1910 and 1922, he and his wife had four children. Father Pavel was a well-known academic and lecturer.

When the Bolsheviks took over Russia in 1917, they made Father Pavel an offer: either go into permanent exile, or do scientific work for the soviet regime. He was eager to do the work, especially given the way the soviets were seeking to integrate long-separated fields of knowledge.

Father Pavel chose scientific work–but on his terms. What were Fr. Pavel’s terms? Donald Sheehan, co-translator of Iconostasis writes,

Fr Pavel looked every inch the priest. In exemplary defiance of powerful atheist masters, Fr. Pavel would stride into crowded lecture halls dressed in cassock, cross, and priest’s cap. The scientific vigour of his lectures could not, for the authorities, eradicate the image they saw before them: for even the most rigid of atheists could not gainsay the iconic reality of his priesthood (16).

And while he could not publish his scientific work, he wrote theological works, the final one being his 1922 Iconostasis.

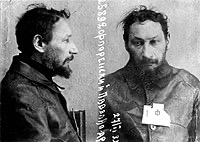

In May 1932, Fr Pavel was made the highest member of the scientific committees. But on February 25, 1933 he was arrested.

Wounded By Love

The circumstances of Father Pavel’s arrest arrest are convoluted.

There was a professor named Gudulianov. Gudulianov was arrested five years prior. He was told that if he wrote a statement about supporting Nazis, and implicated a number of people including Fr Pavel, he and his family would escape imprisonment. If he refused, he and his family would suffer further punishment.

Gudulianov chose to write the false statement. But he needed others to sign it, including Father Pavel.

Now Father Pavel did not succumb to the authorities at any time. He believed that signing false statements and colluding with the soviets would harm the soul. But while arrested, Father Pavel was given a meeting alone with Gudulianov. Gudulianov pleaded with Father Pavel to sign the statement of repentance for colluding with the enemy or Gudulianov and his family would be killed. But what about Fr Pavel’s wife and four children? What would happen to them if Father Pavel were given the death penalty?

Such circumstances threw Father Pavel into a grave spiritual crisis. Donald Sheehan continues,

[Fr. Pavel] would well have known that to participate in the lies of state violence robs the soul of every shred of spiritual integrity, and that once truly begun, the destruction of integrity is nearly impossible to halt. Yet he would also know that spiritual integrity in Christ has unfathomable depths, for in that bare OGPU room in late February 1933, Fr. Pavel could not have helped but discern in the faces of the Soviet authorities the very faces of the Jerusalem rulers who had crucified Christ. And what is the Crucifixion apart from the willingness to accept in unconditional love the violence that is given? Moreover, Fr. Pavel would have seen before him the face of his false accuser begging him for life. And if Christ in crucified agony had prayer for his implacable murderers to be forgiven, what was he to do with this cringing accuser?

On June 26, 1933, Father Pavel was sentenced to ten years in the gulags.

While in the gulags, Father Pavel continued his intense scientific work, but always as a priest by serving “the needs of the poorest, most ravaged prisoners”(22).

A crucial image survives the darkness–Fr. Pavel saved the scraps of bread from his own meagre meals and fed them to the starving and dying. Everything had been stripped away from him–social meaning, dignity, freedom, family, psychological well-being, and physical health–except this irreducible core of priesthood in Christ: this is my body; take, eat (22).

On 8 December 1937, Father Pavel was executed most likely by a single shot in the back of the head. His body was never recovered.

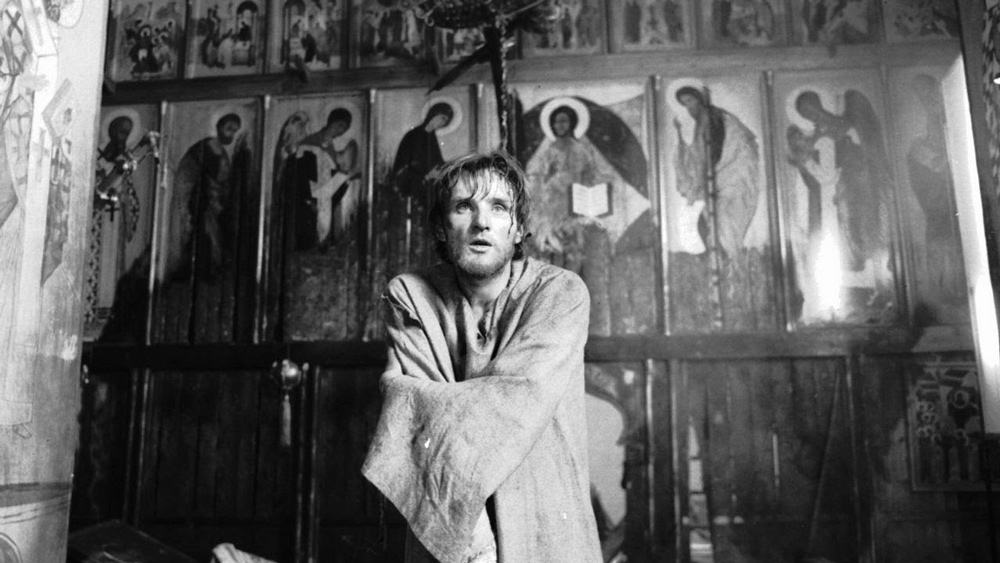

An icon is a symbol that points toward and participates in that which it points. In this way, Fr. Pavel was a living icon who in his suffering and persecution never ceased to enter into it bearing the image of Christ the Logos Himself. By feeding, e.g., his scant rations to prisoners, “there is nothing he can either do or say–he must now simply and only be; and in this simplicity of being he reveals who he truly is in Christ”(25). This is, according to Donald Sheehan, the guiding principle of Iconostasis.

Let’s go into Iconostasis a little bit, dipping here and there in this dense rich text, to uncover how we might understand the creating of icons in various forms.

Iconostasis

What does the iconographer do? How does he or she create?

Like the Samaritan woman to Christ, we say to the icon painter: Now we believe—not because you bear witness to the sanctity of the saints by your icons but because we ourselves can hear coming out from them, through your brush work, the self-revelation of the saints and not in words but in their holy countenances. We ourselves can hear how the supremely sweet voice of God’s word, the true witness, penetrates into the essence of the saints by its super sensible sound and brings their entire being into perfect harmony. For it is not you, O icon painter, who has created these images; it is not you who has shown to our joyous eye these images; it is not you who has shown to our joyous eyes these vividly alive ideas; no, they themselves have appeared within our contemplation, and you have simply taken away the obstacle that hid their light from us, for you have helped strip away the scales that covered our spiritual sight. And because you have helped us, we now see no longer your masterpiece but the wholly real images themselves. I gaze into this icon and say in myself: this is She Herself, not Her image, but She Herself who, with your help icon painter, I am contemplating. As through a window I see the Mother of God, the Mother of God Herself! And it is She Herself that I am now praying to face to face and not to an image! A window is only a window, and the board of an icon is merely wood, paint, and finish. But through the window I behold the Mother of God, a vision of the Most Pure. Yes, iconpainter, you have shown Her to me, but you did not create Her; rather you have parted the veil so that She, who was behind it, now stands as a real experience not only for me but also for you; and She appears to you and is found by you, but She is never invented by you even in the strongest current of your highest aspiration.

What does the icon painter do to create such windows into heaven from which the wood and paint and finish become the Mother of God? This is true Art and thus true authentic creativity. But can this apply to writing? By that I mean, can writing also become such a doorway? Writers like Michael O’Brian and Eugene Vodolaskin certainly seem to think so.

But more by Florensky …

An icon remembers its prototype. Thus, in one beholder it will awaken the bright clarities of his conscious mind a spiritual vision that matches directly the bright clarities of the icon; and the beholder’s vision will be comparably clear and conscious. But in another person, the icon will stir the dreams that lie deeper in the subconscious, awakening a perception for the spiritual that not only affirms that such seeing is possible but also brings the thing seen into immediate felt experience. Thus, at the highest flourishing of their prayers, the ancient ascesis found that their icons were not simply windows through which they could behold the holy continuances depicted on them but were also doorways through which these countenances actually entered the empirical world. The saints come down from the icons to appear before those praying to them (71-72).

Similar experiences have occurred less frequently (but still connectedly) to persons who were not following any ascetic practices of prayer at all: that is, a sharp penetration of a spiritual reality into the soul, a penetration almost like physical blow or sudden burn that instantly shocks the viewer who is seeing, for the first time, one of the great works of sacred icon painting. There is not the slightest question in such experiences that what is coming through the icon is merely the viewer’s subjective invention, so indisputably objective is its impact upon the viewer, an impact equally physical and spiritual … [And] we can only describe experiences of seeing it as a beholding that ascends (72).

There is so much more here from Florensky that I can quote, for instance when we stand before an icon in this “seeing that ascends,” …

The fires of our lusts and the emptiness of our earthly hungers simply and wholly cease; and we recognize the vision as something that, in essence, exceeds the empirical world as something acting upon us from its own dominion (42).

But what is the life of the icon painter? How does the icon painter create such art? Florensky describes the experience, the occupation of the icon painter as that of one “who sees that the world is sacred”(70).

The authentic artist is one who sees the world as sacred and filled by God. Such a way of seeing is the point of departure for art.

To the truly creative, the presence of canonical tradition frees the artist’s energy for new attainments, releasing it from the necessity of sterile repetition; the demands of canonical tradition—more precisely, the gift from mankind to artist of canonical tradition—is therefore for the artist not an enslavement but a liberation (79).

Florensky critiques the artist who rejects the form and beauty of canonical tradition to simply make something up from the sub-conscious, for “such an artist is throwing away the perfection of form and is, instead, taking hold subconsciously of the wrecked fragments of forms whose perfection—now accidental and imperfect—can only be wholly subconscious memory; and such work is called ‘creative’”(79)

There is in the above passage a key distinction between true and relative art: that the artist is not concerned about his own truth (whatever that means anyway), “but rather the objectively beautiful and artistically incarnate truth of things—and he cares nothing at all about pride’s mean-spirited question whether he is the first or the hundredth to speak this truth. If the work is true, then it establishes its own value”(80).

There’s a critique here on modern art and its deviation from any form at all that would exist in the real world. The icon painter is capturing things as they truly are, and thus opening us up to the transcendent itself. It is on this point that I am puzzled by, for example, Davor Dzalto’s The Human Work of Art in which, somehow, iconography is somehow almost on par with modern art. Nevertheless, it seems that the lack of formal restraints placed on modern art leads to its aesthetic undermining such that a urinal becomes a work of art by simply being placed upside-down. Conversely, it’s the placing of limits on iconography that allow for a freedom of expression on the part of the artists in creating a piece of art that liturgically points one to God, His Holy Mother, the choir of the saints, etc. And perhaps this is what Florensky could more broadly mean by holy fathers as those who create true art.

Hence the creative process leads the artist into “the objectively beautiful and incarnate truth of things,” and therefore into the really real world, not as some kind of ‘relative truth’ that one discovers merely for himself, but rather that same truth that is universal and therefore for all.

Just so—the work of art lives, and the artist who bases his work on the canonical tradition … discovers in and through the canons the energy to create works wherein reality is the true object of their meditation, wholly certain in the knowledge that his work (if free) will never duplicate another’s—though his actual concern is not with that issue but with the truthfulness shown in the work (80).

An icon painter’s life is therefore not simple. Because they are raised in the ecclesiastical hierarchy above ordinary lay people, they must therefore practice a greater humility, purity and piety, a profounder practice of fasting and prayer, and a more constant and deeper contact with their spiritual father. Thus the bishops consider their icon painters as people ‘higher than ordinary’ … [in] actuality icon painters always put themselves under disciplines stricter than any given to them, becoming genuine ascetics in the exact sense of the word (90).

Because the artist is conveying that which is beautiful and true; because he or she creates to invite others into a reality that transcends the disenchanted and ‘material’, there is a responsibility he or she has to live in greater “humility, purity, and piety.”

I believe this applies to writers as well, as we saw for instance in the letter by Michael O’Brien. There is a responsibility the artist has to God to live more set apart from the world and its proclivities, its pride, its fantasies, and thus pursue a life “higher than ordinary”—to “become genuine ascetics” in the true sense of the word.

Florensky elaborates …

The deeper question is: if eternity must be witnessed in and through the icon, can this occur through the work of someone who is himself alienated from true spirituality? … Hence the ascetic demands placed upon icon painters.

Florensky cites the Hundred Chapters Council (Russia, 1551), where the precise conduct of clergy and iconographers were laid out.

Let it be known, then, that the icon painter shall be meek, humble, and reverent, neither filled with vain talk nor empty laughter, not quarrelsome, not envious, not a drinker of spirits, not a thief or a murderer; and above all things, that he shall sustain in great mindfulness a pure chastity of soul and body, and that if he cannot sustain a pure chastity of the body he shall marry a wife by the lawful sacraments of matrimony; and that always and everywhere the icon painters shall attend constantly to their spiritual fathers, telling them everything always and living always according to their teachings about fasting and prayer and all the ascetic disciplines, doing so with neither embarrassment nor willfulness, and always the true wisdom of humility …(92).

This applies more than just to icon painters or writers, poets, sculptors—it applies to everyone. And as such, the life of the icon painter detailed in the Hundred Chapters Council expands out to the Christian life itself. Thus the artist returns to the fundamentals of Christian life and spiritual practice, not to become an artist qua artist, but rather to become an artist qua saint. The purpose is to become a saint, and let the art flow out of the abundance of grace and mercy and love as he or she draws closer in union with God and with all of creation.

What would art become if we applied these standards of the icon painter? What would writing become? What would film become? What would music become? What would painting become? What would architecture become? If art flowed out of the holiness of the artist, out of the saintliness of the person?

What would the world be like if all of us lived this way—for it’s not just for artists, but for saints which we are all called to become.

This goes back to Father Pavel and the gulags: the simple icon of a falsely accused man offering his meagre rations to the poorest and illest prisoners, and thereby radiant with the image of God.