Tolkien and Lewis were two exceptionally prolific and creative writers. But what did they know about creativity, and what can we glean from them today?

Know ye that the Lord he is God: it is he that hath made us, and not we ourselves; we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Psalm 100:3

Creativity Flowing Out of Relationship

This whole blog up till now has been about creativity—not a ‘how to’ on creativity like some of those books that veer into ‘self-help’, or something merely about ‘the creative process’ as a kind of ‘technique’.

Instead, I’ve written about creativity in its relation to Christian spiritual practice, i.e, to create out of a relationship with God Himself, with Beauty Himself, with the Logos Himself.

In this relationship, creating stuff is something that comes out of a broader set of gifts we are given to use in various circumstances, such as being hospitable or charitable or speaking into someone’s life when you don’t even know you are, or being “an instrument of God’s peace.”

There is so much being written today about the creative process, about how to become more creative—or worse yet, how to become ‘an artist’—which leads to a kind of madness and self-obsession. Desiring to ‘become’ an artists, or seeking to be called or admired as an ‘artist’ is a particularly painful illness born of self-obsession. Even putting artistic work under the banner of ‘Christianity’ can be particularly dangerous, for it attempts to ‘sanctify’ the ego.

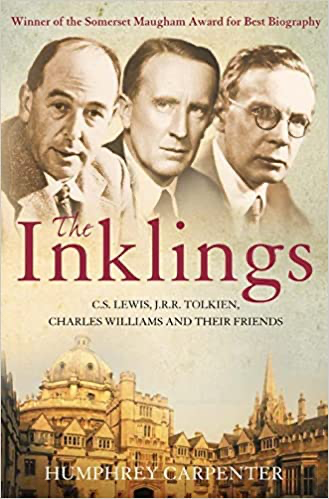

The Inklings as Instruments in the Hands of God

This is where the Inklings come in, and in particular Humphrey Carpenter’s book entitled The Inklings. Aren’t the Inklings, particularly C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, simply made up of people in a rather at times clumsy way being used by God to open the masses to the enchanted world? Would you have called any of them saints? Tolkien seemed curmudgeonly and back-biting—especially about Lewis—and Lewis regaled in his love for beer and smokes. (One of my favourite stories is when Tolkien criticized C.S.Lewis for his unslaking predilection for beer. “Jack told me he was cutting beer for Lent,” Tolkien scoffed, “which simply meant he was down to two pints a day!”) Were they obsessed about becoming artists? Did Tolkien seek to be hailed as the greatest artist of his time?

No. They both simply wanted to use literature as a way to open people to Beauty, God, and Truth. One story in Humphrey’s book is when Lewis came across some science fiction—a far cry from the classics of literature he was teaching in his classes at Oxford. But he saw science fiction as a way to reach more people than, say, Dante could. He told Tolkien that they needed to put their creative juices together and write some science fiction books.

Nevertheless Tolkien did write about creativity—he called it “sub creation with God.”

Sub-Creating with God

Here’s Carpenter from his book entitled The Inklings …

“The argument of Lewis’s Christianity and Literature was paralleled by Tolkien’s lecture on Fairy Stories, delivered the same year that Lewis’s essay was published. In this lecture, Tolkien declared—as he had told Lewis on that September night eight years earlier—that in writing stories man is not a creator but a sub-creator who may hope to reflect something of the eternal light of God.

“In that lecture, Tolkien had quoted from the poem that he had written for Lewis, recording something of their talk that night under the trees in Addison’s walk …

Man, Sub-creator, refracted light Through whom is splintered from a single white To many hues and endlessly combined In living shapes that move from mind to mind. Through all crannies of the world we filled With elves and goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light, And sowed the seeds of dragons—‘twas our right (Used or misused), that right has not decayed: We make still by the law in which we are made.

To Tolkien and Lewis, writing stories reflects something of the eternal light of God—indeed even story writing! And in reading the poem that we are sub-creators with God because we are working under the laws that He has a priori established—“we make still by the law in which we are made.”

Stealing Fire from Heaven

Years later, Thomas Merton would criticize the Promethean understanding of creativity, namely that creativity is indeed that which man has stolen from the gods and claimed as his own. The Promethean orientation to creativity and creative genius was not for Lewis and Tolkien—they understood our place in the cosmic order: we are refractors of Light, albeit splintered. We are called to become gods through grace, not to become God.

C.S. Lewis also had plenty to say about creativity as that which stems from the image of God placed in us—he indeed wrote the Forward to St. Athanasius’s On the Incarnation.

Here’s Carpenter again …

“‘What’ [Lewis asked] ‘are the key words of modern criticism?’ Creative, with its opposite derivative ‘spontaneity’, with its other opposite ‘convention’; freedom contrasted with rules. We certainly have a picture of bad work flowing from conformity and discipleship, and of good work breaking forth from certain centres of explosive force—which we call men of genius.’

“This [Lewis said] was in conflict with the New Testament, where he claimed it is often implied that all ‘creation’ by men is at its best no more than the imitation of God, and in no sense original at all. From this he concluded that the duty of a Christian writer lies not in self-expression for its own sake, but in expressing the image of God. Applying this principle to literature, Lewis said, ‘We should get as the basis of all literary criticism the maxim that an author should never conceive himself as bringing into existence beauty or wisdom which did not exist before but simply and solely as trying to in terms of his own art some reflection of eternal Beauty and Wisdom”(62).

Poetically One Dwells …

Hence writing Beauty means that one is engaging in the Beautiful, one is encountering Beauty Himself—not as a way to somehow extract creativity through ritual (that’s what those in the occult attempt to do), but in relationship.

Here’s Saint Porphyrios …

“Take delight in all things that surround us. All things teach us and lead us to God. All things around us are droplets of the Love of God—both things animate and inanimate, the plants and the animals, the birds and the mountains, the sea and the sunset and the starry sky. They are little loves through which we attain to the great Love that is Christ.

And the culmination of this “taking delight” in Beauty for Saint Porphyrios …

“For a person to become a Christian, he must have a poetic soul. He must become a poet. Christ does not wish insensitive souls in His company. A Christian, albeit only when he loves, is a poet and lives amid poetry. Poetic hearts embrace love and sense it deeply.”

The Way Up is the Way Down

To become ‘poetic’, to encounter Beauty is part of the upside-down Kingdom of Heaven. The ‘world’ teaches one to become a poet by a kind of spontaneous rebellion against anything ‘conformist’. That a poetic soul is cultivated by establishing one’s ‘own truth’.

But in Christianity, one cultivates a poetic soul to encounter and be encountered by Beauty Himself. The object of the poetic soul is God Himself, not writing books or doing slams or getting published and making it big.

Rather, if there be any creative work, it is simply the output of a soul that’s become poetic in its pursuit of and relationship with Beauty and Poetry Himself.