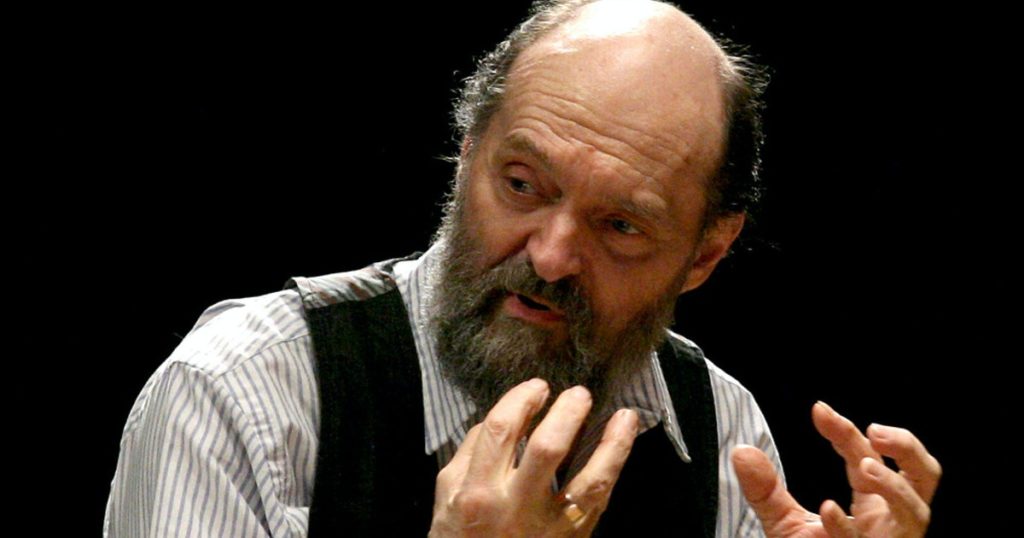

In this post, Arvo Pärt shows us what it means to create art as a product of spiritual practice. That creativity and humility are interconnected.

How long, O you sons of men, will you turn my glory to shame? How long will you love worthlessness and seek falsehood? … But know that the Lord has set apart for Himself him who is godly; the Lord will hear when I call to Him.

Psalm 4: 2-3

Have You Thanked God for This Failure Already?

One of my favourite videos of Arvo Pärt is his honorary doctorate acceptance speech at St. Vladimir Seminary. Pärt, in a spirit of humility and even it seems brokenness, approaches the podium and begins his speech.

In the Pühtitsa Monastery, Estonia, “Have you thanked God for this failure already?”

Have you thanked God for this failure already? What an opening line … Have I ever thanked God for my failures? No. Maybe in retrospect, years later, when I’m in a good mood … But never in the moment.

In this address Pärt is showing us an orientation to creating art that is distinct from the way one might conventionally think of it.

One imagines the composer or writer or painter in the heat of the moment creating out of a state of unflagging ecstasy. Not that creating this way is inadequate, but Pärt shows us something different. He shows us a way of creating that is deeply connected to the way of the heart.

Pärt continues …

These unexpected words were said by a little girl, I remember exactly, it was July 25, 1976. I was sitting in the monastery’s yard on a bench in the shadow of the bushes with a notebook. “What are you doing? What are you writing there?” asked the girl who was around ten years old. “I’m trying to write music, but it isn’t turning out well,” I said. And then the unexpected words from her, “Have you thanked God for this failure?”

Purify the Soul Until it Begins to Sound

When I first saw this video clip, I wept. It watched it again, and wept again. And just now I put it on, and got all choked up. There is a palpable honesty in this interaction between the composer and this little girl. Who is this little girl? Pärt doesn’t tell us; but the honesty of the interaction and the way the girl’s words bore such a sharpness of truth, makes me wonder if indeed she was an angel or a saint.

Here’s more …

The most sensitive musical instrument is the human soul. The next is the human voice. One must purify the soul until it begins to sound. The composer is a musical instrument, and at the same time a performer of that instrument. The instrument has to be in order to produce sound. One must start with that, not with music. Through the music the composer can check if the instrument is tuned, and to what key it is tuned.

Make Me an Instrument of Your Peace

The writer is the instrument. Reminds me of the prayer of St. Francis of Assisi: Lord make me an instrument of your peace. As the instrument, the writer, artist, creator, must enter a process of purification through prayer and service to God. Otherwise, it’s as if one has a Stradivarius violin and leaves it out in a downpour. The rain will soak into the wood and destroy not only the functionality of the instrument, but also the form.

We are created in the image of God. When we live in the wrong way, when we make life all about our passions, our envies, our temptations, we cannot expect to have much good to express in our art. For the soul, that image of God within us that we are called to bear in all aspects of our life, including art, becomes distorted and darkened. I think this is what Pärt is talking about here.

God knits man in his mother’s womb, slowly and wisely. Art should be born in a similar way. To be like a beggar when it comes to writing music: whatever, however, and whenever God gives.

Here Pärt affirms the image of God within us, and that we are carefully and wonderfully made by our Creator. God knits as the Holy Trinity: there is a fatherly grace, there is a divine word and inherent logic in the creating of a person, and there is illumination, inspiration, by the Holy Spirit. Art should be born in the same way: with a kind of grace, with logic and structure and care, and with an illumination of the Holy Spirit in us. To enter the work as prayer, not as ambition or ego. But to be like a beggar: Lord however and whenever and whatever You want me to create.

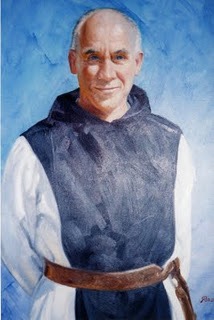

Merton’s Stories he Wouldn’t Write

Such an orientation to God in our creative work reminds me of what Merton said once in one of his journals. He listed all the story ideas he wasn’t going to write, because they emerged from a place of ego and ‘curiosity’, rather than out of silence and prayer. It doesn’t mean we don’t write with a passionate fury, with melodious pace and rhythm. It doesn’t mean that our creating doesn’t stir up things within ourselves that are painful or exhilarating or lustful. But we create it remaining close to God, ever seeking His Love and inspiration.

Pärt continues with this lovely line about how we ought to write, compose, create …

We shouldn’t grieve because we write little and poorly, but because we pray little and poorly, and lukewarmly, and live in the wrong way. The criterion must be ‘everywhere and only humility’.

This is the right orientation, the right priority for creating art as Christians—get the heart right first. So much teaching about creativity is spent on the process of creating. But Pärt shows us something other, an orientation to God, our fellow human, and all of creation. We must not concern ourselves about whether we’re creating enough, whether we have enough time to create, or just the right circumstances to create. Rather we should be concerned primarily about our hearts, our souls, how we are living.

Creating and Doing Heart Work are One and the Same

Are we truly being loving? Is our creative work furthering or hindering the Kingdom of God within us? Is our creating coming out of a place of humble union with God, or is it all about our egos. I forget where I heard this, but it was said that you can tell if your ego is in something when you are prevented from doing it and you react harshly.

How Pauline are these next words from Pärt …

Music is my friend. Ever-understanding, compassionate, forgiving. It’s a comforter; the handkerchief for drying my tears of sadness, the source of my tears of joy, my liberation and flight. But also a painful thorn in my flesh and my soul; that which makes me sober, and teaches me humility.

Whatever we’re doing at a high level, whether writing or composing or painting or consulting, it should drive us further to humility–not pride. Pride is the downfall of life, period. It is considered the primary sin; the sin from which all others flow. And it kills our ability to create. If I’m struggling with creating something, and a friend of mine is killing it in his own life, that should drive me to love and rejoicing not envy. If I’m feeling envy, then I will despair and won’t be able to create.

If the work is taking me through a process of humility, if the work is a thorn in my flesh, then I must use it as a way to get closer to God–and therefore it becomes the greatest gift. This paradox of being friend and thorn is something in Pärt I resonate with. There’s something sad and beautiful, broken and glorious about creating in this way.

In this way, our seeking artistic expression comes out of an expression of our gratefulness to God for all things, including standing in the midst of another failure.

One Response