How do we understand the metaverse in the context of creating beauty? Reiner Maria Rilke’s experiences in nature are reminiscent of a far-gone pre-technological age.

For the Lord is a great God and a great King above all gods. In his hand are the depths of the earth;

the heights of the mountains are his also. The sea is his, for he made it, and the dry land, which his hands have formed.

Psalm 95:4-5

The Disembodied Mind

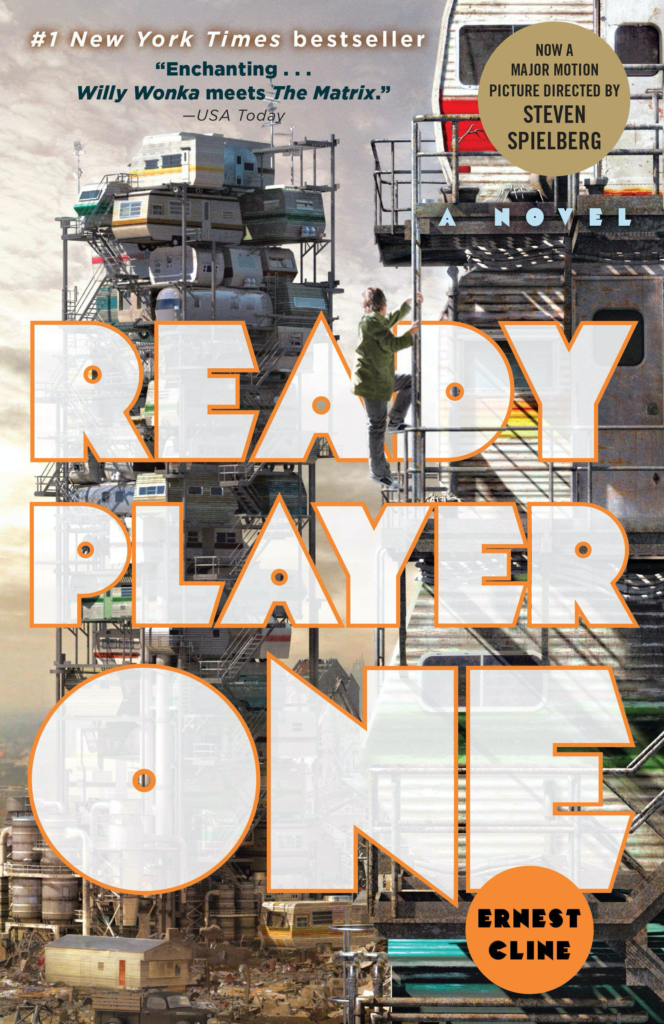

The metaverse has come up in a number of conversations as of late—this drive to enter a world that is apart from the real world, the world of stuff, of matter. A friend of mine sent me a link to a metaverse world. I ‘entered’ it, and found ‘myself’ surrounded by pearly white buildings—a kind of futuristic landscape. I navigated around, awkwardly so, until I found a building that looked interesting. I ‘walked’ in. When I walked in I realized that it was a kind of art gallery. There was art on the walls. I could click on the description to read what it was all about. Next to that button was one that read ‘Make an offer’.

For those who may not know, there are ‘pieces’ of art that are selling for millions of dollars. Millions of dollars for a digital image made up of zeros and ones. There is nothing ‘material’ about it, and yet people are paying real currency for it. Not only that, but people are buying whole ‘plots of land’ and building buildings in the metaverse—and again paying in some cases thousands if not millions of dollars!

What is this drive to as it were flee the natural world for the digital world? What are people seeking in the metaverse? Has the real world become simply ‘boring’? Perhaps we are looking for a world that corresponds more to our imaginations, our fantasies, than settling for the harsh reality of matter.

Back to the Natural World …

The metaverse is the world of man’s own making. It is un-reality. There is nothing ‘virtual’ or veritable about it. The underlying principle of the metaverse is a rejection of the natural world. For me, as a Christian—one who asserts the natural world as a gift from God for my enjoyment and benefit—I want to become more deeply rooted in the natural world, which means overcoming the urges to flee from it into digital media. Saint Patrick says it beautifully in his prayer:

I arise today through the strength of heaven. Light of sun, Radiance of moon, Splendour of fire, Speed of lightening, Swiftness of wind, Depth of sea, Stability of earth, Firmness of rock.

In the natural world, the Lord is everywhere present and filling all things to the extent that if you cut open a log of wood you will see Christ.

In the natural world, when offered back to God, water becomes a substance of blessing and healing and baptism, wine becomes the blood of Christ, bread becomes His Body, oil becomes a substance of healing and blessing, wood becomes crosses and alters and churches, paint becomes icons, wool becomes a rope to open one to prayer … It is in such a world that one raises beyond the bondage of one’s own thoughts. In such a world there is communion with God, the saints, and one another.

Conversely, the metaverse is pure illusion. To affirm the metaverse is, therefore, to reject God.

Rilke as Poet, Artist, and Human Being

Rainer Maria Rilke had a vibrant life of correspondence. In writing letters, it was as if his thoughts were brought to life that influenced his writing. One of his mentors was the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Rilke spent a number of years living with Rodin and serving him as a kind of assistant. When one looks at the way these two men inhabited nature, one catches a glimpse not only of what being human is but also how far from this we are as modern western deconstructionists.

Here’s a letter to his friend Karl von der Heydt …

“. . . Only the very great are artists in that strict yet only true sense, that art has become a way of life for them—: all the others, all of us who are still only just busying ourselves with art, meet on the same wide roads and greet each other in the same silent hope and long for the same distant mastery . . .”

So how is art “a way of life” for those who are masters?

Here’s a portion of a letter to his wife about a typical afternoon with Auguste Rodin:

“[Rodin] was always on the move with Madame Rodin …, in the woods, always wandering. At first he would set up his paintbox somewhere and paint. But he soon noticed ash in doing this he missed everything, erecting alive, the distances, the changes, the rising trees and the sinking mist, all that thousandfold happening and coming-to-pass; he noticed that, painting, he confronted all this like a hunter, while as observer he was a piece of it, acknowledged by it, wholly absorbed, dissolved, was landscape. And this being landscape, for years,—this rising with the sun and this having a part in all that

is great, gave him everything he needed: that knowledge, that capacity for joy, the dewy, untouched youthfulness of his strength, that unison with the important and that quiet understanding with life. His insight comes from that, his sensitivity to every beauty, his conviction that in big and small there can be the same immeasurable greatness that lives in Nature in millions of metamorphoses … In the evening at twilight when he comes back from the rue de l’university, we sit at the rim of the pool near his three young swans and look at them and talk of many and serious things. Also of you. –it is beautiful the way Rodin lives his life, wonderfully beautiful.”

Rodin and Rilke were settled into the natural world. There was time. There was space. There was a chance to ponder the banality of a twig broken off from a tree:

“Rodin looked at it for a long time, felt its plastic, strong veined leaves and finally said: so, I know that forever now: it is an elm (“c’est l’orme”).”

This is one example of how Rodin’s art was a way of life for him. Rilke, Rodin affirmed the natural world and in it found great beauty and inspiration for art.

On Solitude

And where does the natural world lead one? Into solitude. Solitude was an essential part of Rilke’s poetic life. In his Letter to a Young Poet, Rilke writes the following on solitude …

Embrace your solitude and love it. Endure the pain it causes, and try to sing out with it. For those near to you are distant…”

We often enter the social to fix the pain of solitude—the metaverse included. It’s interesting that one can be both alone and yet with many people in the metaverse. You can sit physically alone in your room, at your desk that gazes out the lonely window, and yet still be with people in another world. But that’s not solitude. Solitude is the ability to sit alone with yourself and God and just be.

Here’s Father Anthony Bloom …

“As long as the soul is not still, there can be no vision. But when stillness has brought us into the presence of God, then another sort of silence, much more absolute, intervenes: the silence of a soul that is not only still and recollected, but which is overawed in an act of worship by God’s presence.”

God is found in silence, in stillness, in solitude. It is therefore good to learn to sit with yourself and God without having to do much else. Just sitting there—you and God … Entering into His goodness, and receiving His Love, and being silently thankful whether in your studio or office, or out in nature …

Return to the Beginning

And last from Thomas Morton’s book on solitude …

“Our glory and our hope—We are the Body of Christ. Christ loves us and espouses us as His own flesh. Isn’t that enough for us? But we do not really believe it. No! Be content. Be content. We are the Body of Christ. We have found Him, He has found us. We are in Him, He is in us. There is nothing further to look for, except for the deepening of this life we already possess.”

Glory to God for all things!