In a world of 24-hour news and countless opinions at our finger tips, combined with a yearning for enchantment, we must enter into deeper silence.

For God alone, O my soul, wait in silence, for my hope comes from Him.

Psalm 62:5

CROWDS ARE GANGS

There is something about being in a crowd that makes me want to be silent. In some ways I’m becoming more quiet the older I get—though I feel moments of injustice more, and am prone to getting ‘fired up’ in public if people or bureaucratic authorities are acting like something out of a Kafka story.

Nevertheless, I was at dinner one evening—a business dinner. And almost immediately when we sat down, the question was posed about what one thought of a very complex current political affair. For the most part people were just spouting off opinions without any real understanding of the nuances of the event (the back room deals, the myriad parties involved, the complex back stories, etc—all the states of affairs that congeal into the ‘event’).

Look we all do it … But there’s something important about stepping back from such conversations and asking oneself ‘What do I truly know about this event? What sources am I drawing from to formulate my opinion? What underlying conflicts are at work or being manifested in this opinion? Is what I’m saying or opining about really worth saying?’

That’s just political and current states of affairs—things that my father of confession told me today “that are unnatural for us as humans to know and be concerned about.”

Nevertheless, as e.e. cummings once stated, “Crowds are gangs.” And what’s the way through such crowds? …

THOMAS MERTON ON KIERKEGAARD’S SILENCE

The noise of crowds is one thing, but what about the experiences we have with God, our experiences of faith? Are they in an even different category of ‘language game’? Is there something about them that is actually not conducive to language at all? …

I’m reading the first volume of Thomas Morton’s Journals: the time Merton is living in New York just at the outset of his baptism into the Catholic Church, and his movement towards monasticism. His journals are filled with all kinds of quotes from the books he’s reading. I was pleased when I came across a section of entries on his reading of Kierkegaard, a philosopher I still enjoy reading from time to time, and who I continue to wonder about what would have happened if he would have come in contact with Orthodoxy. Merton parks over a series of entries on Kierkegaard’s thoughts on silence in the midst of encounters with the enchanted world: of God, saints, and angels …

Merton writes,

Kierkegaard has an interesting notion of a vow of silence necessarily imposed upon a man capable of the kind of faith shown by Abraham in the trial over Isaac. This faith is beyond heroism because it is incomprehensible. Heroism is only possible in the realm of the universal. This is beyond ethics, beyond the universal [Kant’s ‘ought’], beyond the intelligible, and once more particular. Abraham is an individual in the presence of an Absolute Personality. This relationship is incomprehensible.

Here’s the line that is so powerful …

To try to express it—for Abraham to try to express it, would be a terrible temptation to hypocrisy or sacrilege. Hence the vow of silence. [And thus] he [Abraham] has to endure this martyrdom of being incomprehensible, absurd.

THE VOW OF SILENCE IN THE FACE OF THE ABSURD

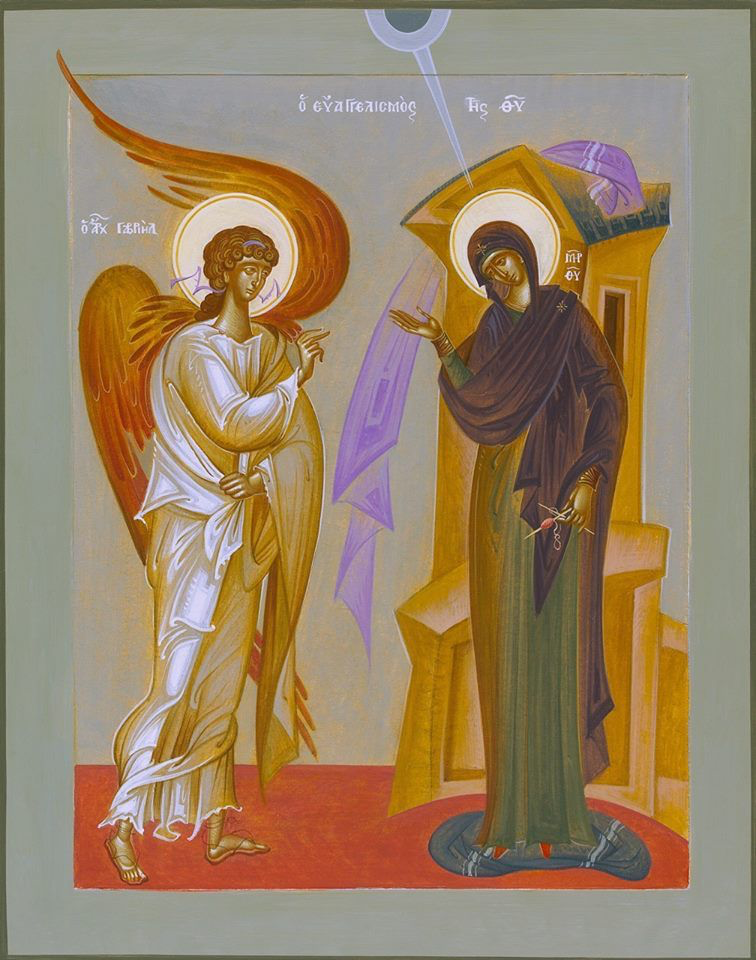

The vow of silence becomes an existential response to the absurdity of saintliness, of encountering God, of having been ‘opened’ to the glory of God and the heavenly hosts the reality of which is scandalous to the banality of reason, of the paltry news of the mere ‘ethical’, of the nihilism of ennui of being ‘nice’. It is the scandal of ‘yes’ as Merton writes next on the Holy Theotokos—but also of Mary Magdalene and St Gabriel of Georgia.

The similar vow of silence is imposed on the Blessed Mother by the incomprehensible mystery of the annunciation: “Be it done unto me according to Thy Word!” This dreadful and magnificent and terrifying annunciation of the angel: “The Spirit of the Lord God will come upon thee.” “Be it done unto me according to Thy Word.” This is beyond heroism: there is absolutely nothing theatrical about it, nothing spectacular. if it could be explained, this would be heroic. Because it is incomprehensible hence the void of silence. She must remain completely alone with this immense and terrific responsibility which no one is able to understand … That is the highest thing of all—silence: The final culmination of Christ’s teaching, the test of our faith, beyond all teaching, is His disappearance from the tomb. Nobody saw the Resurrection.

Merton, 265.

The vow of silence is the appropriate response to a hyper-rational yet completely insane and disenchanted world; a world in which rationality is insanity and insanity is rationality, and in it the naked irony: that even at its most absurd, reason remains ever distanced from comprehending the absurdity of the enchanted mystical world, hence the vow of silence. In fact, the more rationality becomes absurd, the farther away it moves from the absurdity of the real and thus seeks to a priori negate it.

In the same way the Mystery of the Annunciation is so extreme that to men it seems strangely neutral, it cannot be grasped. Unbelievers can’t even make much of scoffing at it; they try and their insults never get anywhere near what they would like to say—they seem powerless. So also with the Resurrection: it is so incomprehensible that it is even beyond blasphemy.

Yet our Blessed Mother, in the Annunciation, was left absolutely without protection for the insults of every unbeliever. She was the only one who ever saw the angel and, Kierkegaard says, the angel was sent to her: the angel was not sent to announce the mystery to the whole world that men might more easily believe. if we have any faith at all, we are able to share in that same insult: that those who blaspheme our Blessed Mother may also think us mad for believe in in the Annunciation. But it happens that those who have the most faith are those who appear less heroic: Saint Francis before Alvernia [where he received the Stigmata] was a passionate wonderful saint: and after it, a silent, hunched up little man, hiding his hands.

Merton 266-67

SILENCE IN THE MIDST OF THE TECHNOLOGY

Again heroism as that which exists within the arena of ethics, of rationality; the hero as one who affirms that a moral order ‘exists’—but where on that spectrum between hero and villain do you put the saint? Not even negating the hero works into some kind of anti-hero, for it presupposes a thing that one is within—the realm of the rational, the disenchanted. The holy fool as one who transcends the concepts of ‘holiness’ and ‘foolishness’ and anti-heroism. And thus one enters the vow of silence, for who will understand anyway? Even among Christians—I included!—is the absurdity of the enchanted world sloughed off and rationalized through cliche and ostentation …

The vow of silence idea in Kierkegaard is something you come across everywhere, because radios are forcing men into the desert. The world is full of the terrible howling of engines of destruction, and I think those who preserve their sanity and do not go mad or become beasts will become Trappists, but not by joining an order, Trappist in secret and in private—Trappists so secretly that no one will suspect they have taken a vow of silence.

Merton, 267

How much more when the radios are no pocket televisions with an endless surfeit of information, random movie clips (no longer full movies anymore—just 30 second clips!), real-time news, scenes of murder and shameless sexuality; the first thing one pics up in the morning, and the last thing one puts down before bed—it is our fifth appendage to the point that being away from our phones for more than five minutes sends one into a fit of panic. How much more this silence and secret monasticism! …

The higher vow of silence is not for most people. I don’t think it is to be sought after … [A] man must still lose himself secretly in doing good works of faith and love in the universal sense. This comes before any higher vow of silence, but this vow of silence is important too. It is by this silence that we preach: by that we cannot preach. In either case we must seek silence. I think that is indicated not only by the increase of unbearable sound in the world. Why was St Philomena kept hidden for seventeen centuries? If not to teach us secrecy.

Merton, 267

SILENCE AND THE ART OF WRITING

Isn’t silence the modus operandi of the writer? Why talk when you can write? The position of the writer is silence: the word conceived in silence, and the work consumed—at least in modern times—largely in silence. Maybe that’s why Kierkegaard and Merton wrote so much on silence. Nevertheless, silence is demanded of one in the context of the transcendent.

(I must say this parenthetically … Kierkegaard most likely would’ve become a monk, especially had he been exposed to the desert—now he obviously knew of St John Climacus! But what if he had been met by a bona fide monk of the desert? What if an anchorite would have come to him in 19th century Copenhagen? …. The imagination runs wild …)

Sometimes I fall into temptation to speak about things that are ‘absurd’, when I should remain silent about it. It is not good to open the oven door when cooking, and it is likewise not good to open the door of the heart with the mouth—at least that’s what my father of confession tells me … Yet I do it all the time thus reducing the mystery to the crudity of language and ‘categories of reason’ and the cynical expressions and rolling eyes of those around me …

The way through is to enter deeper into silence.