Jon Fosse is an artist whose Septology along with other works can be considered liturgical writing. He reveals how existentialism can be infused with holiness.

I wait for the LORD, my soul waits, And in His word I do hope. My soul waits for the Lord More than those who watch for the morning–I say, more than those who watch for the morning. Psalm 130

Liturgical Writing

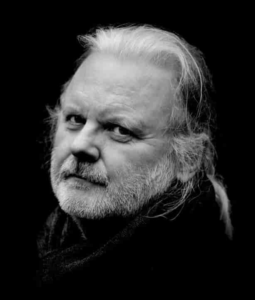

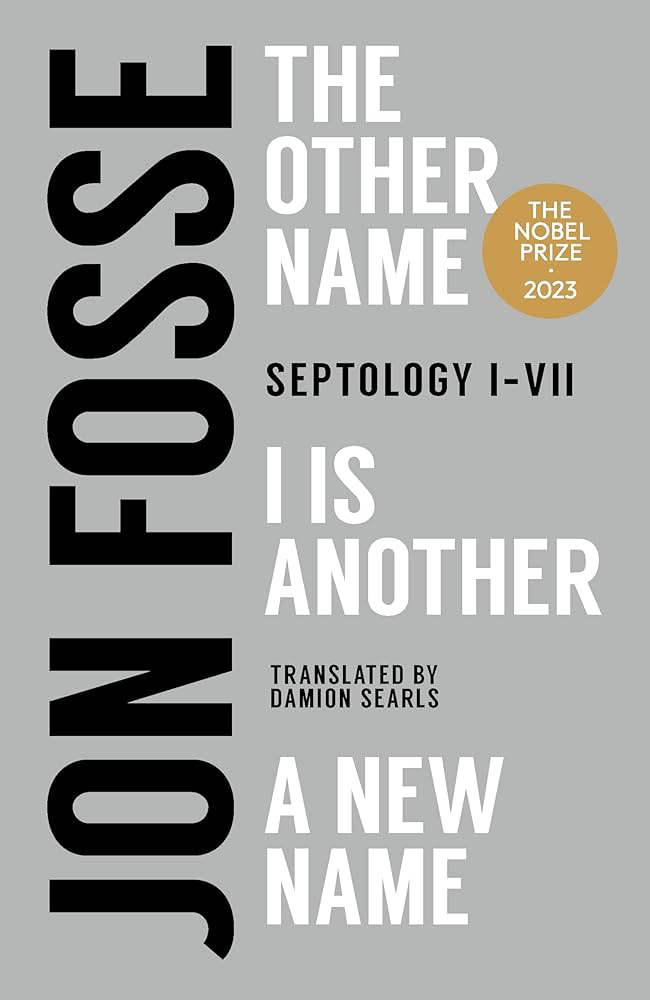

Jon Fosse is one of my favourite writers of all time—and I only heard about him through a Guardian article in October 2023 announcing his awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature. I immediately ordered Septology on Amazon and dove into it. … It was a tough dive in, however: the prose is slow and repetitive. You are in the mind of the protagonist whose thoughts inch forward and cycle back around only to inch forward again. If you’re an action junkie, then this book will drive you nuts. But for those who love stream of consciousness and existentialist fiction like I do, Fosse is wonderful.

There is another aspect to Fosse’s writing that is truly special and profound: how he draws us into his liturgical writing, how his writing is ritual and our reading of it becomes ritual too. Let’s go deeper …

The Background

One of the things that struck me from the article was that Fosse began writing Septology in 2013 after he had been through recovery from alcohol addiction and had converted to the Catholic Church. I was thus excited to see how existentialist fiction and Catholicism could come together.

(The alacrity I felt was actually the complete opposite of the deflation of my 3rd year existentialism class at the University of Toronto. There, sitting behind the young Canadian actress Sarah Polly—who was taking the class, I inferred, as part of her research for her role in David Cronenberg’s ‘Existenz’—I became immediately disappointed when the professor read out the philosophers’ names we would be studying, two of whom, out of the three, were Christians: Gabriel Marcel, Soren Kierkegaard, and the third—definitely not a Christian—Friedrich Nietzsche. I was excited about reading Nietzsche!)

As I read through Septology I found myself at home, finally, with a writer who I felt was like me: he saw the world in a similar way, and sought to bring the light of his Christian faith through the typical darkness of existentialism. I found myself weeping over passages of this book as the light of his prose rose over the page and illumined my soul.

The Eucharist

One of the big themes of the book is the Eucharist. Fosse’s protagonist Asle is a recovered alcoholic who ruminates about going to Mass in between reflections on his life, his deceased wife Ales, and his art. The story takes place four days before Christmas, unfolding as it leads up to Christmas Eve. The protagonist, Asle, reflects on his life, his art, and his deceased wife. (Oh—and there are no periods throughout the entire book!) Nevertheless, here’s an example of Fosse’s writing on the Eucharist …

… and I feel a strong need to take part in mass again, and be forgiven, and take communion, and usually I always drive to Bjorgivin on Christmas Day to go to mass, even though I like the simple mass on normal weekdays better. I go to high mass on Christmas Day … (534).

Going to mass, taking the eucharist, and receiving the remission of sins weighs heavily on Asle—he needs it for his life. He yearns for it as the salve that it is for his broken heart and weary soul. Asle continues in a beautiful description of his preference for those small everyday masses that are contrasted by the bravado that is often accompanied with Christmas.

but there’s a completely different spirit in the simple everyday masses on Sunday mornings, then it’s almost full in St Paul’s Church, and there’s singing, yes, a choir, and full organ music, yes, all things considered it was very nice but for me it was the quiet moments with just the words from the priest and the answers from the people that were the best masses, and when people there, five or six or seven of us, stood up to take communion, there was a wonderful sense of atonement, yet, of peace that came over everything, I think, and maybe I’ll want to paint pictures again if I just go to mass and sit peacefully and pray a silent prayer as the host, Christ’s transfigured Body dissolves in my mouth and I become part of Christ’s mystical body, become part of the communion of saints, and when as a part of it I turn towards God in silence … (534-5).

The smallness and meekness of the everyday mass that ties beautifully into the meekness and smallness of St Mary and the birth of Christ. But note also the tie in of the mass to the creation of art: “… and maybe I’ll want to paint pictures again if I just go to mass again and sit peacefully and pray a silent prayer as the host, Christ transfigured Body dissolves on my mouth and I become part of Christ’s mystical body, become part of the communion of the saints …”

It reminds me of the Catholic iconographer and writer Michael O’Brien whom I’ve written about both in this blog (link) and in my book Creativity and Becoming (link). For O’Brien the Eucharist is core to the creation of art because it is the life of Christ Himself that he partakes of. For Fosse too, the Eucharist is fundamental to his life and writing.

Holiness and Prayer

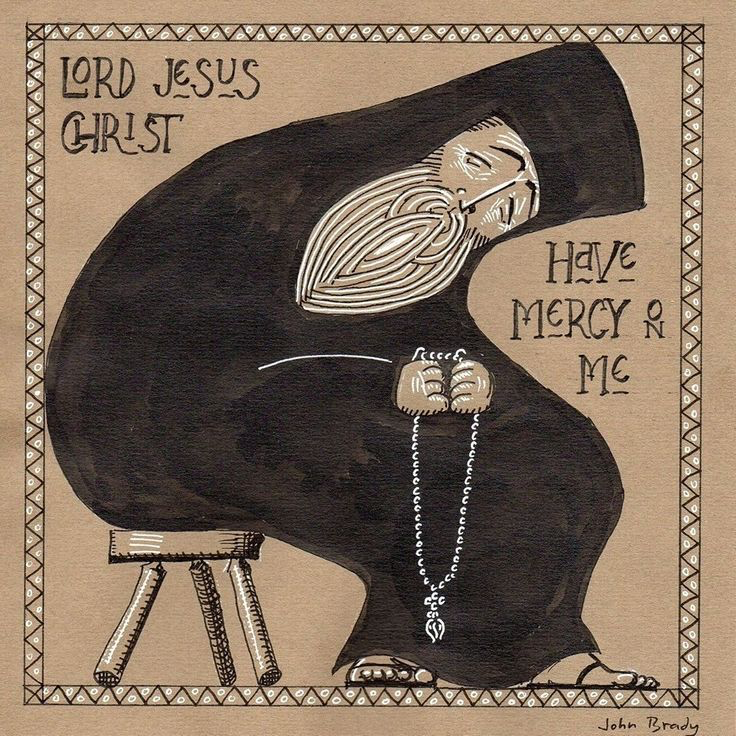

Along with the Eucharist, the story is woven together—well, each section is woven together—by the Rosary and the Jesus Prayer (again—the alacrity I felt! Electric!). At the end of each book, Asle prays the Jesus Prayer with his Rosary, one, he notes, of many he has that his wife Ales gave him over the years. The way the prayer penetrates the silence of the prose, of Asle’s rumination, prayers that take him, his surroundings, and indeed us the reader, into the enchanted world, in to the heart of Christ and St Mary themselves.

… and I move my thumb and index finger up to the first bead which is between the cross and the set of three beads on the rosary and I say to myself Our Father Who art in heaven Hallowed by they name Thy kingdom come Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven . . . and I move my thumb and finger up the first bead in the set and I think I usually sleep if I either say the Jesus prayer or Ave Maria and then I see the words before me and I say I say inside me Ave Maria Gratia Elena Dominos cecum Benedicta . . . and I move my thumb and fingers up to the second bead and I say inside myself Hail Mary Full of grace The Lord is with thee Blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb Jesus Holy Mother of God Pray for us sinners . . . (186).

Thus Asle enters sleep with such prayers from his mind to his finger tips, as if a kind of canon he follows. And again and again, as a literary ektania, the second book concludes with …

And I hold the brown wooden cross between my thumb and my finger and then I say, again and again, inside myself, as I breathe in deeply Lord and as I breathe out slowly Jesus and as I breathe in deeply Christ and as I breath out slowly Have mercy and as I breath in deeply On me (276).

Indeed, the rhythmic structure of the prayers at the conclusion of each book serves as a ritual, a liturgy, that forms the real structure of the book, as if wrapped, as if the entire prose is wrapped with a beautiful rosary and even a black wool prayer rope, around it. It’s as if the ancient desert monks break into the modern European silence of Fosse’s prose and illumine it with striations of light as if through the mouth of a dank cave.

To me, there’s nothing like it! His book is a long sighing prayer to our Lord Jesus Christ and His holy Mother. The book ends with the protagonist Asle in the midst of his own death and the sigh from his heart …

. . . and I a ball of blue light shoots into my forehead and bursts and I say reeling inside myself Ora pro knobs peccatoribus nunc et in hora

Or, “Pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death.”

Septology as Liturgy and Icon

How an artist like Fosse can bring together like a painting, like an icon, the Divine Liturgy and the three great prayers of the Church—the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary, and the Jesus Prayer—in the midst of the shadow of existentialist prose is something indeed to marvel at. Fosse found Christ at the end of his rope, in addiction, in despair and sadness, and seems to share with us a glimpse into his deeply spiritual life that for him, as for all of us who have stumbled our way in and out of baptism, is nothing less than salvation and healing from our self-inflicted wounds.

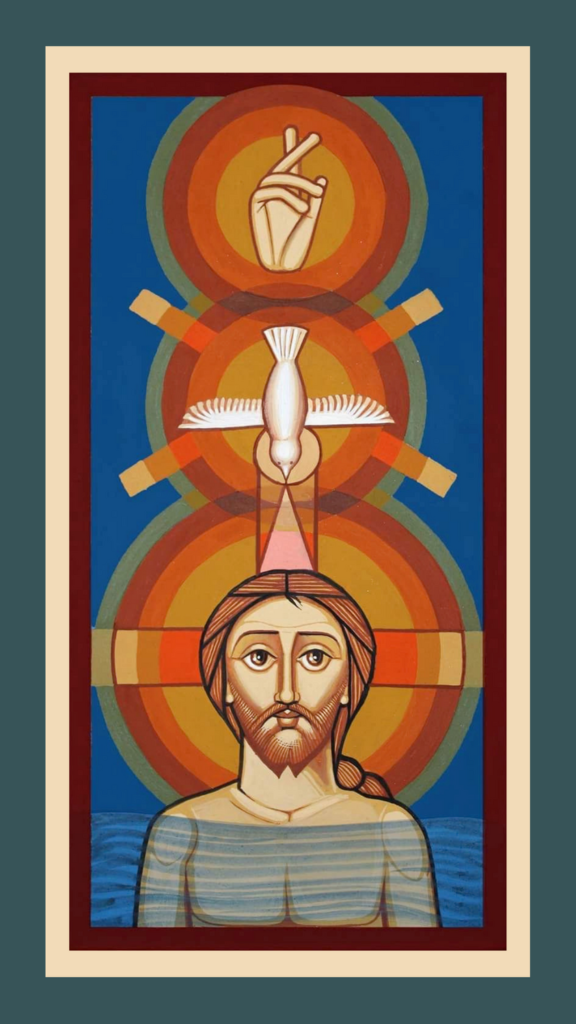

And one cannot help but see baptism as the opening of the book, of this extended prayer, in the epigraph of book one …

“And I will give him a white stone, and on the stone a new name written, which no one knows except him who receives it.” Revelation.

Is this not what we receive at baptism—this anticipation of receiving such a stone with a new name that only God knows but will be revealed to us, the name that we inherit by adoption or like the bride who receives the bridegroom’s last name? The book opens with new life, the birth of a new life, purified by water and spirit, and ends in the mercy of Christ at death.

But this scripture from Revelation is followed by …

‘Dona nobis pacem.’

Which means “Grant us peace,” which, again, is a liturgical prayer. The Epigraph ends with,

Agnus Dei

“Lamb of God”, which, in the Catholic Mass is sung or recited during the breaking of the Bread, and that includes the plea “ … qui tolls piccata Mundi, dona nobis paem,” which means “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.”

Not Christian Fiction. Rather, Liturgical Writing

Septology is a powerhouse work of ‘liturgical fiction’—something I have not read ever before as one new to Fosse’s work, and one who resonates with existentialist literature that finds its rest, its peace, in Christ. It is not a Christian book per se—and thus he finds his company among writers like Flannery O’Connor who did not want to write Christian fiction—yet filled with the holy, the sacred, the liturgical. And I guess that’s what I love

so much about Septology and Fosse himself: like O’Connor, Fosse paves the way for other artists who don’t want to write Christian fiction but want to infuse, illumine everything they write with the Light of Christ, like nature and all of our lives—indeed life itself. Fosse is thus an inspiration for readers and writers like me who love existentialism, but love the Church even more; who want to capture the burden of existence while presenting occasions for—through plot, character, and voice—the work, and the reader him or herself, to be drawn beyond it to the Other, the Uncircumscribed Logos.

Note that I have left out the central plot of the book hoping to tempt you to read it and discover for yourself the beauty and redemption of this wonderfully sad yet joyful story of loss, despair, forgiveness, redemption, and transcendence.