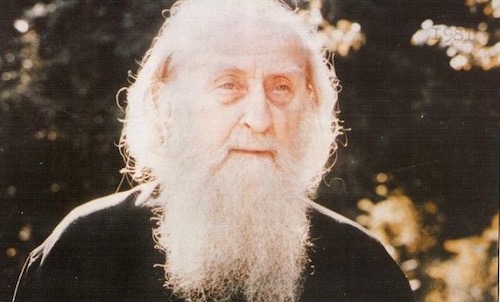

This post continues the thread of creativity and the spiritual life of the Christian through the iconography of Elder Archimandrite Sophrony of blessed memory (1869-1993).

Blessed is the man who walks not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor stands in the path of sinners, nor sits in the seat of the scornful; but his delight is in the law of the Lord, and in His law he meditates day and night.

Psalm 1:1-2

Writing about a saint reminds me of the way the Jesus Prayer was practiced before the divine gift of the prayer rope: the monk would have a pile of pebbles that he would cast into a basket with each prayer. The pebbles are light, but when they add up, the basket is heavy. In this same way, I find taking on a subject like Saint Sophrony or any saint for that matter–I can only write a single pebble and toss it into the great basket of his life. Saint Sophrony pray for me!

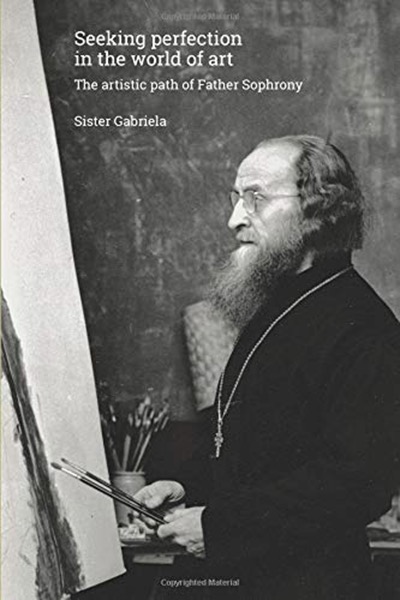

There is a wonderful book about Elder Sophrony written by a nun named Sister Gabriela, entitled Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony. Sister Gabriela is a member of the monastic community Father Sophrony founded called the Community of Saint John the Baptist in rural Essex, England.

In the book Seeking Perfection in the World of Art, Sister Gabriela gives us a glimpse into Father Sophrony’s artistic life. Here we see how the artistic path of Father Sophrony led him for extended periods of time away from art itself and into the time horizon of pure prayer.

The battle between art and prayer, that is, between two forms of life which require the whole of man, continued within me in a very intense manner for a year and a half or two years. In the end, I was convinced that the means at my disposal in art would not give me what I was looking for. That is, even if I could intensely sense eternity through art, this awareness is not as deep as prayer. And I decided to give up art–which for me was a terribly high price to pay.

The isolation [of Mount Athos], coupled with the profound stillness of nature all around, favours prayer of the deep heart and thought of the great calm of the Kingdom to come. The slow eastern rhythm of Athonite life–in absolute contrast to the stupefying beat of our contemporary mechanized existence–adds a precious ingredient of spiritual comfort to this chosen place, since it helps one forget the temporal and plunge into contemplation of eternal mysteries.

When Father Sophrony abandoned art, he attended a seminary in Paris; but prayer continued to pursue him which drove him from his studies to Mount Athos.

Sister Gabriela describes that in this world set apart for prayer, a place of endless kairos, Father Sophrony did not have time to paint–“his new life encompassed him totally.” All that creative energy he had earlier given to his art was now concentrated on prayer. “Prayer became both garment and breath to him, unceasing even when he slept.”

Here’s Father Sophrony in his own words …

Prayer is infinite creation, far superior to any form of art or science. Inspiration meant for me the presence of the power of the Holy Spirit within us. This kind of inspiration belongs to a different plane of being from that which the artist or philosopher knows, though his, too, can be seen as a gift from God. But it does not bring union with God Himself, or even intellectual knowledge of Him.

Reading and contemplating Father Sophrony’s words leads to myriad questions …

What is the creative act?

How does it lead to God?

What are its limits?

How is art infused with God?

Can writing a story be like writing an icon?

Father Sophrony, Michael O’Brien, Arvo Pärt, John Tavener, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn, and on and on–Christians who sought God through the making of Art.

What is the nature of this pursuit?

It reminds of me of what Arvo Pärt said during his acceptance speech at St. Vladimir’s Seminary …

We shouldn’t worry about writing poorly, but rather praying poorly and luke warmly, and living in a sinful way.

Thomas Merton … so many writers and artists …

Tarkovsky … Rublev …

Yet Father Sophrony ditches art for prayer, and then, out of and through that kairos, continues at times to paint.

It says in Seeking Perfection that while on Mt. Athos, Father Sophrony “absorbed the centuries old traditions, observed the frescos, icons, and all the other ecclesiastical art … he especially liked the wall paintings of the monasteries of Docheiariou and Dionysiou.

As a hermit in his cave in Mt Athos before he became a spiritual father, [Father Sophrony] found that he had spare time. He ordered the necessary equipment and technical notes from Mother Theodosia [a Russian graphical artist who became a nun] and started painting icons. Thus he was among the first to renew iconography in its traditional form on the Holy Mountain, the iconographic style which then prevailed on the holy mountain was an Italian Renaissance style.

And yet, just as painting seems to fire up again, Father Sophrony turns again to prayer.

For Father Sophrony, submerging himself in ever deeper prayer and knowledge of God was of far greater importance [than art], a fact he writes about in different places.

The heart is the well into which we dip our buckets for water of inspiration. Are we thirsty? Thirsty for what? If the heart is empty and dry and we reach down into it for inspiration for our painting or writing or sculpting or what have you, what inspiration will we draw from?

And what is the end or ‘telos’ of our prayer? To create art? To be productive? Or is it what it’s intended to be: to grow in loving union with God, and to see everyone and everything through the eyes of love.

How easy it would be to slip into an orientation to prayer as a kind of transaction: I’ll spend my 30 minutes in the morning so that God will give me ideas and inspiration for art …

Father Sophrony’s orientation to painting is indeed suffused with courage and an authentic pursuit of God–“Ah, I’m done with art for a while. I need to draw closer to God in prayer.”

This loving union with God is also the pathway for fully becoming our true selves, which is the source of authentic art. Thomas Merton says a lot about this.

Am I willing to give up writing for a time for prayer?

To be honest … maybe …

The temptation is always to get good and busy, or cut things short to get to creating something.

Another way of approaching it can be to see prayer and creating in an integrated way, not as a dualism. Can my creating be prayer?

Nevertheless, in response to this temptation to get good and busy, I like this quote from Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation

“Be silent in the presence of God and find your salvation.”

If you’ve read this little crumb and are looking for something more extensive on the life of Saint Sophrony and his life of art, check out this excellent article in the Orthodox Arts Journal.

And feel free to offer a comment below. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

2 Responses

Thank you 🙏

AMEN!!!