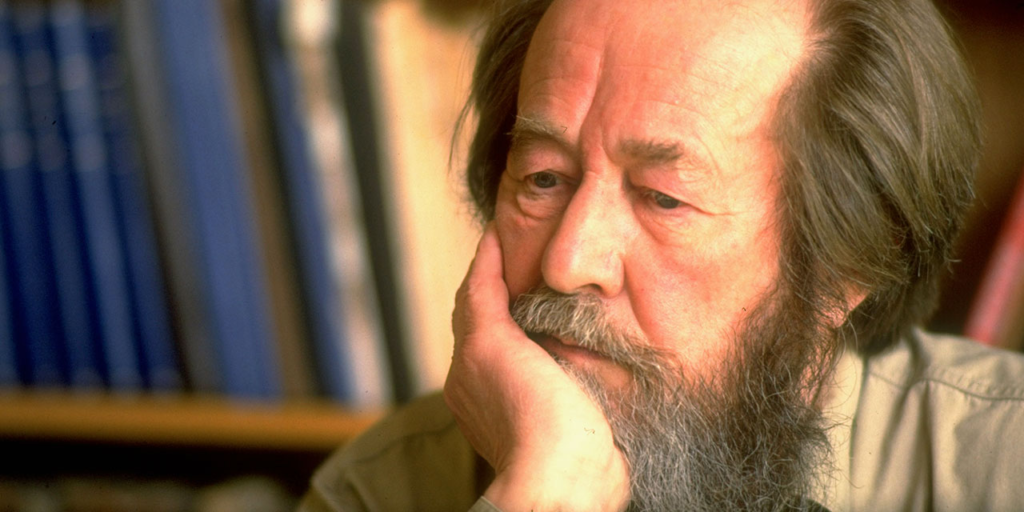

Alexander Solzhenitsyn shows us how to take our creative vocations seriously in the face of many distractions, set backs, and the unflagging pressures of time.

My heart overflows with a good theme; I address my verses to the King; My tongue is the pen of a ready writer.

–Psalm 45:1

So How are You Feeling Today? …

In a previous blog I wrote that despair is not artsy, and the image of the self-loathing artist isn’t cool. But let’s go beyond that to how you might feel about the work you do.

I heard a priest once talk about the temptation of some to avoid the things they’re good at in order to do the things they hate and that they’re not good at as a way of humility. But what is the point of that? When you do what you’re good at, and exercise a gift you’ve been given by God for His glory and the edification of others, that is a service to God and the world.

But when you’re doing that thing you do, do you believe it’s important? Do you use it as if it’s a gift you’ve been given that is precious and needs to be used?

How to Thrive as a Writer by Saying No

I’ve been reading the post-exile writings of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, entitled Between Two Millstones. Between Two Millstones is a ruminating rambling set of books that are polished forms of something one would find in Solzhenitsyn’s own journals. And like reading someone’s personal journals, some of what you find in Between Two Millstones is interesting and some of it is rather pedestrian and even long-winded. In the book, Solzhenitsyn writes a lot about his life in the United States, the myriad articles he wrote, and speeches and interviews he gave warning the US about the threat of communism, defending fellow Russians and their stance against Bolshevism, and pages upon pages of rather maudlin accounts of his travels (which if you’re into it you might get a chuckle over as I did, particularly the chapter about his trip to Japan—priceless!).

One area of his life I wish he had devoted more pages to was his writing. At the time of Volume 2, he was buried in the work of his historical novel of the Russian Revolution—a work he was so devoted to that it dogged him to no end for over a decade, particularly when he felt the pressure to write articles, give speeches and interviews, or respond to the innumerable invitations for meetings, visits, and doctoral degrees and other honoraria. It is clear throughout the book that writing was the most important thing he could possibly do with his time.

Wouldn’t an invitation to Oxford or Berlin for an honorary doctorate degree be particularly enticing? Not for Solzhenitsyn! In his words, it would “dry the juices up” …

Even though I am out of fashion in the west, an avalanche of invitations has been descending on me for all these years—in countless numbers. Invitations to speak, to come and accept a prize or an honorary degree, to send a message of greeting to a conference, to a gathering. . . . If I answered myself I would dry the writing juices out of my hand, for each answer is exactly the same: I am busy, I cannot interrupt my work, I do not go to any events. … And these are of course very worthwhile invitations—to become an honorary member of the Scottish Academy of Sciences, for instance, or the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts—but I’d have to, on the exact appointed day, in Edinburgh or in Munich.

And here’s the clincher:

Am I to tear myself away and go? Quite impossible, just as it would have been to travel from Zurich to Oxford—devastating for my work. Or invited by an old organization … to receive the Friends of Lithuania medal. … But if I didn’t say ‘no’ in this case neither could I in a dozen others. … So no, I refuse.

After reading this passage about Solzhenitsyn’s polite declinations for the sake of his writing I was struck for about a month. It wasn’t as if Solzhenitsyn was writing a fourth and fifth volume of The Gulag Archipelago that would be read by the masses—no. He was writing a novel–in multiple volumes! How many people read six volume novels these days about the details of the Bolshevik Revolution? Solzhenitsyn didn’t care. To him, it was the most important work of his life, and nothing was going to pull him away from it—at least that’s what he led himself to believe. (If you go farther into volume 2 you’ll see he was lured away all over the place, including Japan; and even when he vowed never to leave his study again, he couldn’t hold himself to it.)

In Solitude You’re Happy …

In solitude you’re happy—you’re a poet! As Pushkin discovered when comparing his creative periods in seclusion with those in the bustle of society.

Solzhenitsyn loved the solitude of his home in Vermont and the quiet pastoral life. The solitude helped him find his focus and work Un disturbed. He didn’t have telephone or television in his writing study. What would that look like today with 24/7 mobile phone use!

But as for me, I seem to have no sense of the passage of time: I’ve now already spent over two thousand days following the same regimen, always in profound tranquility—something I’d feverishly dreamed of throughout my soviet life. There’s no telephone in the house where I work, no television, I’m always in fresh air (following the Swiss custom the bedroom windows are always open, even in freezing weather), living on healthy American provincial food, never once having been to the doctor for anything serious, plunging head first into the icy pond at the age of sixty-three—and still today I feel no older than my fifty-seven years of age when I arrived here—and even a great deal younger.

The Pursuit of a Deep Calling

The great Russian writer lived with a sense of calling, of vision, and he dared to work hard and persistently at it. His life was set up in a way that fostered his writing. His surroundings, the food he ate, how he slept at night, and moments of recreation were all integral to optimal creativity. He remained disciplined to stay at his desk even at the expense of accolades and honoraria. Such a serious pursuit of his artistic life led him to write,

But even the young man’s feeling that I haven’t finished developing yet, either in my art or my thought, is something I still feel as I approach sixty-four.

What a poignant observation. He’s still developing. The work isn’t done. He’ll keep going daily, growing as a writer and thinker and artist.

Did he understand himself to be a writer?

Yes.

Did he take that calling seriously?

More so than even many other famous writers.

It’s to see, know, and understand what your work is and then live in a way that fosters it. Not even a doctorate degree could pull the man away from his writing table. This is a pattern among great writers, artists, and craftsmen—they know what they’ve been given to do and they do it tirelessly.

The rigour, focus, seriousness that Solzhenitsyn applied to his calling as a writer is probably the greatest take-away from my reading of Between Two Millstones.

Going Pro

In my own life, sometimes I treat writing like it’s a guilty pleasure—something I need to slip away and do when there’s a spare moment. But a shift must take place when the writing is considered serious work, and an important part of the life of the writer—they know it, and everyone around them knows it.

Stephen Pressfield—my writing coach who doesn’t know he’s my writing coach—calls this shift ‘going pro’.

It’s when you decide that regardless of whether or not you’ve been published, whether or not you’re successful, whether or not you have it all down, you’re making the shift to writing more seriously than ever before.

Pressfield writes …

What happens when we turn pro is we finally listen to that still small voice inside our heads. At last we find the courage to identify the secret dream or love or bliss that we have known all along was our passion, our calling, our destiny.

Solzhenitsyn lived it. He complained a lot—O he complained!—but he worked tirelessly. The only barriers to his writing were those he imposed on himself. His passion, his dedication to his calling as a writer and prophet, is one of the most inspirational things we can take away from his life. And with that insight, we can refocus our lives and reclaim the gift we’ve been given—to write, to create, and, in any other pursuit that has vision and meaning, to take seriously what we’ve been called to do.

A Playful Digression …

Sometimes when I write in my notebook about Solzhenitsyn, I start writing like him. His style is so authentic, so true to his voice, that I just can’t help but mimic it.

To mimic Solzhenitsyn is to simply complain with concise sentences concluded with exclamation points—it’s that easy! (Throw in some venomous parenthetical statements like this one and you’ve got the gist!) And O the use of the vocative! Here, there, hither and thither—O the pain and anguish of it all! This lawyer and that lawyer, tasteless food here lousy hotel room there! And O the pain of travel all over the world preventing him from truly working! (Even though he is writing numerous articles and presenting innumerable speeches, and meeting the most important people, somehow it’s not his fault that he’s not writing! Somehow he’s being flown all over the world by forces outside his volition! And O how he complains and pines and rants and raves to no apparent end!) O the burden of international fame! If only more could understand the heaviness of it all! The heaviness of just wanting to settle down to write without distraction from the likes of Prince Charles or President Reagan!

But amidst the froth and frivolity, drudgery and dirge—page after page!—of Between Two Millstones you come upon gems like this one …

What wondrous cohesion stems from many mounts, many years of work on this colossus. There are never enough hours in the day. I move from desk to desk, from manuscript to source material, and the joyful feeling that I am doing the most important work of my life never leaves me. (No mater when Alya comes in, she always finds me enraptured, happy). … And so you live this full life for weeks and months and years—how you long to distance yourself from any external encounters, just so that no one bothers you! [O the exclamation point—where’s the vocative?] But that’s precisely when they do come piling and swarming in, masses of them …

“Feeling that I am doing the most important work of my life never leaves me.”

Can You Say When You Write That You’re Doing the Most Important Work of Your Life? …

Can you say that about yourself, about the page of writing you worked on for hours that still doesn’t quite sound good?

Can you say that about yourself even after having written and worked on things that nobody reads or probably will read?

Can you say that about yourself in the face of the many voices that tell you you’re a fake and a phoney and that you need to give up and do something else?

Glory to God for All Things

In all of it, the response should be to give glory to God for all things. To see ‘your work’ not as what belongs to you, but what belongs to Him; something He’s given you to do regardless of success or failures, lawyers and bad hotel rooms and terribly smelling food, or endless invitations for speaking engagements and honourary awards. It is where you need to be here and now. It is where God wants you. Because through the writing He sees something greater—that you become not another writer, but the saint you have been created to become.

Solzhenitsyn knew this. And he pursued it. He was an Orthodox Christian—he even had a chapel built in his house, and was good friends with Alexander Schmemann who appears sporadically throughout Millstones. Solzhenitsyn’s vocation as a writer and artist was deeply connected to His love for God and through that his unflagging pursuit of Truth, Goodness, Beauty, and Justice.

For those of us who are writers and artists and love to create things, this is our true vocation too: to give glory to God in our life and through that, and the struggles therein, to become more ourselves by becoming more like Christ.

Nota Bene: The Digression

It is often the case that imitation and jocular ridicule are acts of flattery and devotion.

Pray for me dear Alexander Solzhenitsyn!