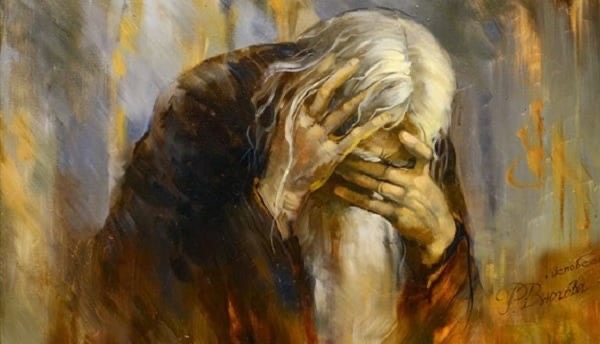

Confessional writing is the opening of the soul to God and others through prose. In this post we consider examples of confessional writing for inspiration.

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord! O Lord, hear my voice! Let your ears be attentive to the voice of my pleas for mercy!

Psalm 130

How Could I …

Some of my favourite writing is confessional prose and autobiographical fiction. There are the obvious ones that are actual confessions like St Augustine’s Confessions and St Patrick’s Confessions. Then there are other forms of literary confession that are more or less evident.

Czeslaw Milosz is an example of one whose poetry tends towards veiled confession, such as this piece entitled How Could I …

How could I Do such things Living in this hideous world Subject to its laws Toying with its laws. I need God, so that He may forgive me I need a God of mercy.— Czeslaw Milosz

My Struggle

Karl Ove Knausgård is another example of autobiographical fiction. His writing is so confessional that he and the protagonist of his books blur into one another. One set of books he wrote are titled ‘Min Kamp’ or ‘My Confession’. His books are so true to nature that a number of his relationships have been sacrificed for his writing—an outcome or consequence he simply accepts. He stated in an interview with his estranged wife Tonje Aursland, who plays a part in several of Knausgård’s Min Kamp books, that sometimes he feels he has made a “Faustian bargain”—that he has achieved huge success by sacrificing his relationships with friends and members of his family. When reading Knausgård I am periodically reminded of Woody Allen’s tragicomic film Deconstructing Harry in which the protagonist is perpetually harassed, even threatened, by the characters of his books coming back to haunt him as real life relationships. For Knausgård, such backlash is simply the unintended consequences of his art.

The only genres I saw value in, which still conferred meaning, were diaries and essays, the types of literature that did not deal with narrative, that were not about anything, but just consisted of a voice, the voice of your own personality, a life, a face, a gaze you could meet. What is a work of art if not the gaze of another person? Not directed above us, nor beneath us, but at the same height as our own gaze. Art cannot be experienced collectively, nothing can, art is something you are alone with. You meet its gaze alone.

—Karl Ove Knausgaard

Why Do We Facebook?

Look at all the writing on social media—people pouring their hearts out on Twitter and Facebook … Writing near tomes on the first-world struggles of their lives. And how many people read it? Many. Though not as polished or well-crafted as literature, such spontaneous acts of confessional writing points to something deep inside us: the desire to be seen, not just in our finest, but at our worst.

That’s probably why I like confessional writing so much. It’s raw and real. It’s not fluffed up. It betrays the fallenness of the human being and its desire to reveal it, make it known, as a means to move beyond it. That’s what makes us human: the desire to move beyond our transgressions to wholeness and healing even if we fail miserably in the process.

The Fig Tree

Ted Hughes was married for a time to Sylvia Plath. Plath was one of the pioneers of ‘confessional poetry’.

This excerpt from her book Bell Jar is disturbing and painful and poignant …

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

― Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

While reading Hughes’s Paris Review Interview I resonated with this statement about confessional writing …

Goethe called his work one big confession, didn’t he? Looking at his work in the broadest sense, you could say the same of Shakespeare: a total examination and self accusation, a total confession—very naked I think, when you look into it. Maybe it’s the same with any writing that has real poetic life. Maybe all poetry, insofar as it moves us and connects with us, is a revealing of something that the writer doesn’t actually want to say but desperately needs to communicate, to be delivered of. Perhaps it’s the need to keep it hidden that makes it poetic—makes it poetry. The writer daren’t actually put it into words, so it leaks out obliquely, smuggled through analogies. We think we’re writing something to amuse, but we’re actually saying something we desperately need to share. The real mystery is this strange need—why can’t we just hide it and shut up? Why do we have to blab? Why do human beings need to confess? Maybe if you don’t have that secret confession, you don’t have a poem—don’t even have a story. Don’t have a writer … [Until] the revelation’s actually published, the poet feels no release.

Ted Hughes, Paris Review Interviews

The desire or need of the writer to confess to a public audience might partly be remnants of a common practice of people confessing their sins before a congregation of others. Another offshoot of this is the public testimony during which one tells one’s story to a group of people about their past (typically graphically ‘sinful’) with their acceptance of or return to Christ.

I heard a priest say once, commenting on work he was doing at a homeless shelter, that alcoholics and drug addicts have no problem confessing their sins—they know themselves very well, how broken they are, and how much help they need. Whereas in contrast, the more ‘successful’ one appears, the more difficult it is for them to confess—their clothes, cars, and upstanding position in society are the armour they have built around themselves to protect themselves from public scrutiny.

And perhaps this is why such confessional writers are so important: they become the medium between the reader and their sins; that in reading the confession of the writer, they are in essence confessing through them.

Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard wrote in a similar way. Just look at one of his most famous pieces of writing, Diary of a Seducer in which the protagonist leads on a young girl only to dump her shortly after engagement. He was writing his own story about his broken engagement with Regina Olson, while providing “the occasion” (an important term for Kierkegaard) for the reader to see his or her own self in the seducer’s confession of seduction and betrayal. In fact, Kierkegaard gives the reader a heads up on his two-way confessional method with the epigraph of Either/Or: “My books are like a mirror: if a monkey looks in, a saint can’t look back out.”

What I really need is to get clear about what I must do, not what I must know, except insofar as knowledge must precede every act. What matters is to find a purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die.

― Søren Kierkegaard

And another … Few can suffer ironically like dear Søren Kierkegaard:

I have just now come from a party where I was its life and soul; witticisms streamed from my lips, everyone laughed and admired me, but I went away — yes, the dash should be as long as the radius of the earth’s orbit ——————————— and wanted to shoot myself.

― Søren Kierkegaard

We Are All Sinners.

As a student in university studying such writers, some of my professors warned against the fallacy of ‘psychologizing’, i.e. reading the author’s personal life into his or her prose. And yet without fail in those instances in which I interpreted their writing in the context of their biography I could gain valuable insights. For from what other experiences do we draw from in writing? The confessional or autobiographical writer makes those connections more explicit.

We are all sinners … and therefore all of us are confessors in one way or another.

This is why many of us are so attracted to confessional writing: part of us marvels at the ability of the writer to bare his or her soul on the page, the other part of us wishes we could have the freedom and unbridled vulnerability to do the same.

That said, there is a gift that confessional writing can provide: that your life becomes an offering for others to read and resonate with and be edified by. In confessional writing our lives, our pasts, our failures, our joys and pains are no longer ours but used by God for others.